Why Natural Monopoly is Regarded as a Necessary Evil

What Difference Does it Make?

Basically, the word monopoly has a negative connotation; hence, recognizing its natural occurrence in the utility industry may seem like a less reliable system to bank on.

Economists have explained that allowing a single corporate entity to monopolize the operations of certain utilities takes away the impracticability of replicating cost-intensive infrastructures and other capital investments.

In return, profits, albeit controlled, will go to the lone provider as this will enable the entity to recover or compensate the cost of money, within the shortest time possible. This will also enable the natural monopolist to provide electricity more efficiently, as fund availability and expenses eventually meet at similar levels.

To better explain this, let’s illustrate by way of example.

Supposing Company A, B and C are all engaged in the business of providing electrical power. It follows that each of these companies would be constrained to install their own power lines, transformers, transmissions, power plant sites and other basic facilities as a means to generate and distribute power to different consumers.

For illustration purposes, let us further suppose that each company had the capacity to spend as much as $20 million to erect, install and render as operational the infrastructures. Naturally, all three companies expect to recover the $20 million costs within the shortest time possible. Still, their selling prices have to be competitive in order to allow all companies to operate fairly by competing in terms of services instead of prices. At the end of the day, all three companies will find it difficult to meet the costs of running and operating the facilities since the expected cash increment has not materialized.

Let’s take the example further by hypothetically taking into consideration a certain community, in which there are about 6,000 households being served. Supposing the rendering of power distribution services were equally divided between the three business entities, this denotes that there is no more room for projecting additional customers. Not unless, however, some of the customers transfer their business to any of the two other companies, which will, of course, be detrimental to the replaced entity.

In addition, it cannot be expected that all of the 6,000 households have the same amount of power consumption. Thus, it is possible that one of the companies is serving more customers but selling less in terms of power distribution. Similarly, another company may be selling more but not all of their customers are in the habit of paying their bills on time.

These circumstances are beyond each company’s control and could likewise render the entity helpless in leveraging prices. Increased prices would result in losing customer patronage, while lowered prices will only drive-down both cash increments and profits. Hence, multiple operators providing utility services in a single community are deemed impractical.

Basing on these circumstances, it became a common contention that a natural monopoly was a necessary evil.

The Independent Operators of the Early Utility Industries

The Federal Power Commission was established in 1920 to coordinate and control hydroelectric power operations but only as a minor arm of a joint administration of the Department of War, Agriculture and Interior.

Basically, they had no active participation in the regulation of the emerging commerce over power generation and consumption.

During the 1920s, the challenges of running a utility company were met through the following system:

1. Additional funds for the cost of building the required infrastructures were obtained from the investors of a holding company. The capital fund provided by the latter was relatively cheaper than borrowing funds from a banking institution.

2. Construction materials and equipment were purchased in bulk and at discounted prices from suppliers as a means to save on costs.

3. Electrical power was acquired from a central station of large power plants as they handled the distribution of electrical services through their interconnections with the smaller utility power plant distributors.

This set-up seemed to provide the ideal solution as an alternative to natural monopoly as far as the trading of electricity was concerned. However, there was a problem in this set-up that was not readily perceived.

In all three aspects, the holding company was at the top of the entire utility trading structure since they also had controlling interests over the suppliers and the large major power plants.

The Existence of a Ubiquitous Monopoly

Technically, the utility companies were merely subsidiaries to the holding companies. It was a pyramidal structure of organization, in which the holding company was at the topmost level and in control over the major suppliers in the middle and the individual utility companies at the bottom level.

However, during the said era, there were no regulations pertaining to limits by which holding companies could invest the funds they managed. Thus, it came to be that the issue of monopoly resided not in the generators and distributors of electricity but in the holding companies that had the resources to invest in every inter-related and interdependent business.

In addition, the service providers and major suppliers were leveraging their own sales in order to recover the cost of capitalization as well as to generate favorable rates of return on the investment (ROI) provided by the holding company’s investors.

Accordingly, there were sixteen holding companies that were technically in control of about 75 percent of the electricity being distributed and sold to the American consumers. During the 1920s through the 1930s, all profits led to the holding companies as they were able to demand higher ROI, higher profits and manipulate stock market trading by encouraging stock market speculations.

In an economy where there is an imbalance of wealth distribution, the only direction it will lead to is economic depression. The monopoly culminated in the stock market crash in 1929 and the 12-year era of “The Great Depression”.

Utilities Operated by Local Governments

Reflecting back to the operations during the 1920s to 1930s, the utility companies that were not affected by the manipulations of the holding companies were the electric service providers that were owned and operated by local governments. These entities delivered electrical services at cost and placed all requirements for construction services, materials and equipment supply under a system of public bidding. Henceforth, the public contracts were awarded to the lowest but reputable bidder.

In this set-up, the members of the communities vote and choose the power plant suppliers with the most reasonable rate and efficient services.

Obviously, the local government provided electricity throughout the community not for profit but purely for service.

The Reactive Laws

Public Utility Holding Company Act (PUHCA)

As a reaction to the discovery of the excesses imposed by the holding companies, the Public Utility Holding Company Act of (PUHCA) was legislated by Congress in 1935. The imposition of the law reorganized the system by reducing the 75% influence of all holding companies to only 15% of the entire electricity generated.

However, this was amended in 1992, by allowing the exemption of holding companies that were engaged in the wholesale of utilities. Unfortunately, this again presented an opportunity for circumventing the law during the same era. Unscrupulous companies like Enron and Worldcom manipulated the condition of the wholesale concept by creating dummy corporations.

This likewise led to stock market crashes, widespread bankruptcies and economic depression. As expected, it also spurred the legislation of yet another reactive law: The Sarbanes Oxley Act.

The Federal Power Commission

In conjunction with the passage of laws and mandates imposed by the federal and state government, Congress likewise voted to empower the Federal Power Commission FPC. The Federal Power Act of 1935 and the National Gas Act of 1938 granted FPC the funds and the power to form a five-member, bi-partisan alliance to regulate the sale and distribution of electricity and natural gas.

Through the years, FPC’s power evolved and expanded, in which its final ruling in 2008 promoted the use of long-term contracts for wholesale electric trading and the use of the “demand response system” for independent operators.

Complex Accounting System of Utility Companies

Under this set-up, consumers have a choice and so do investors. It could be expected that accounting for costs and the methods of income recognition would be complex. Certain issues have surfaced in light of tax regulations vs. investors’ expectations.

Cost capitalization could be deferred by depreciating at twice the rate of the asset’s useful life. However, there are fixed asset components that had shorter life spans due to obsolescence or faster wear and tear due to corrosion. There is also the power plant equipment that was ordered to be decommissioned due to environmental concerns.

In a nuclear power plant, the accounting for fuel rods required the recognition of liabilities once the rod is placed inside the reactor, while the cost of reprocessing the fuel rods are added to the latter as additional costs.

Cash generation units are being established to identify if inflows are largely dependent on certain assets from those that can generate inflows as an independent unit like generating stations. Accounting for them has become critical in connection with decisions to generate power based on expected prices or anticipated demand as well as the efficiency in fulfilling such demands.

Apparently, this complex accounting of the capitalized assets, liabilities and cash-collection shows that the utility industries in the U.S. have come of age, regardless if it is independently operated or government-owned. The history of natural monopoly in the utility industry and all the related developments has debunked monopoly as a primary consideration for the industry’s operation. It’s not the system that is at fault but the ethics that is applied to the system.

References

- By Waltersdorf, Maurice G. –State Control of Utility Capitalization – http://www.jstor.org/pss/789742

- Financial reporting in the utilities industry — http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/energy-utilities-mining/pdf/ifrsutilities.pdf

- Ei River Dam by By Allen Drebert under Public Domain

- Belarus-Minsk-Power Plant-4-1 By Alex Zelenko CC BY SA 2.5

- FEMA - 40819 - Utility crew in Arkansas By Win Henderson under Public Domain

- By DiLorenzo , Thomas J. –The Myth of Natural Monopoly – http://mises.org/daily/5266/The-Myth-of-Natural-Monopoly

- MarignyMG07NOFutilites1 By Infrogmation under CC-A 2.5 Generic

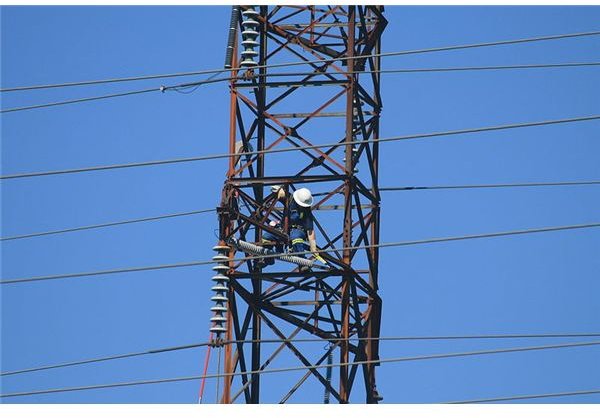

- NB Power worker performs maintenance of a lightning arrestor on a electrical transmission tower in Saint John, New Brunswick By Tew3 under CC BY 3.0