Concepts of Basic Ecology: Competition Within Ecosystems

What is Competition?

Within ecosystems of any kind, from forests to open plains to coral reefs, some of the resources that support survival and growth are finite. Food is the most common category of limiting resource, followed by space. Space can be in the form of territories (which are often also about access to food), or just uncrowded physical living space - think of oysters growing on top of each other’s shells because all need to find hard surfaces in the surrounding mud they live in.

Access to sunlight is important for plants, such as in forests with canopies that block out sunlight from reaching the ground. Within a species, there’s also access to mates, for example, male African lions taking over prides from other males.

Competition occurs when many organisms within an ecosystem want to use the same resources and there isn’t enough to go around. Resources fall into two broad categories: divisible and nondivisible. A divisible resource can be shared by multiple species or groups of species that all use different parts or at different times. Nondivisible resources tend to end up under the control of a single dominant species.

Interference vs. Exploitative Competition

When two or more species want to use the same resource, two types of competition can occur. They can physically fight over it and kill each other off, which is called interference competition. This tends to happen when a resource is nondivisible, and leads to competitive exclusion - one competitor wins and excludes all others from using the resource in that ecosystem or area.

Or, if the resource is divisible, competitors can avoid each other by using the resource at different levels, places, or times. This is called exploitative competition and leads to niche segregation (the subdividing of a resource into separate niches, with one species using each niche).

Symmetrical vs. Asymmetrical Competition

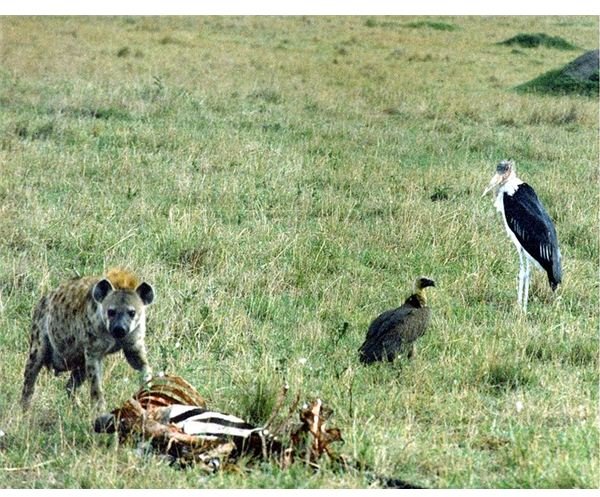

Niche segregation can be symmetrical or asymmetrical. Two equally good competitors will evolve away from each other toward opposite ends of a resource’s range of niches - for example, one species focuses on large food items and the other focuses on small ones, with some small overlap on the medium sized items. The feeding guilds of vultures are a good real-world example. The resource ends up equally divided among all the species (or groups of species) under symmetrical competition.

On the other hand, if one species is superior and one is inferior, the inferior competitor gets pushed out toward the resource’s extremes while the superior competitor doesn’t change much at all. Under asymmetrical competition, one species dominates over the best parts.

Factors that Mediate Ecological Competition

Within an ecosystem that is relatively isolated from outside influences, competitors undergo coevolution with each other, eventually ending up with either competitive exclusion (the loser goes extinct in that area) or some sort of stable setup of niche segregation (could be symmetrical, could be asymmetrical). However, many ecosystems have regular introductions of species from outside the region. When invasion occurs, an inferior species can maintain itself within the ecosystem even though it can’t compete with the resident dominant species; evolution therefore occurs over broader, allopatric conditions (multiple geographically-separated ecosystem areas).

Competition is also mediated by other types of ecosystem interactions, especially predation. If the superior competitor is preferentially eaten by a predator, its population gets reduced regularly, allowing the inferior competitors a chance to access the resources. Ecological disturbances are another way for an ecosystem to clean its slate of competitive conditions and allow the various species to start over.

Finally, the conditions that make one species superior and another inferior are also subject to change. In ecological succession, different groups of species take turns being the best possible fit in the ecosystem, then get outcompeted by the next group. Likewise, cyclical changes like seasons will favor different species at different times, allowing all of them to coexist within the ecosystem.

Reference and Photo Credit

Begon, M., J.L. Harper, and C.R. Townsend. 1990. Ecology: Individuals, Populations and Communities. 2nd ed. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Inc.

Competition over a zebra carcass: hyena, stork, and vulture by Mila Zinkova, used under CC-A-SA 3.0 license