Normal Weather Patterns of the Northwest Region: Factors Influencing Conditions There

Factors Influencing Weather in the Northwest

Normal weather patterns of the Northwest region of the United States are somewhat predictable due to some important variables that influence weather conditions in this magnificent western corner of America. Climate and nature don’t recognize political boundaries, so geographically we are essentially talking about roughly the western middle of the continent of North America bordering the Pacific Ocean and extending inland toward the Rocky Mountains.

Since interactions between oceans and the atmosphere are at the core of most weather patterns, the Pacific Ocean plays a significant role in determining the weather there as do conditions emanating from far to the north and what is rolling in from Hawaii. The many mountain ranges throughout the area generate their own weather patterns due to their towering geographical significance.

As in most weather patterns, the fact that oceans and the atmosphere mirror each other is an important factor in creating the weather the residents of the Great Northwest experience. Due to the vast and stalwart character of the Pacific, it is the slower partner in its endless waltz with the atmosphere. Whereas the atmosphere can change quickly in temperature and liveliness, the Pacific is slower to catch up in its mirroring endeavors. Continuing with that metaphor, the Pacific won’t heat up and sweat or move wildly like its counterpart, the atmosphere, but it certainly tries to keep up as best it can. Its vast store of water is the source of precipitation through the process of evaporation. As you’ll learn by reading about jet streams and their importance, these narrow, fast flowing currents of air (which obviously weren’t discovered or fully understood before the advent of the jet airplane for which they’re named) located near the troposphere also play a part in influencing weather. They push weather all over the world, including the Northwest, and the Polar jets are usually the strongest wind forces of them all.

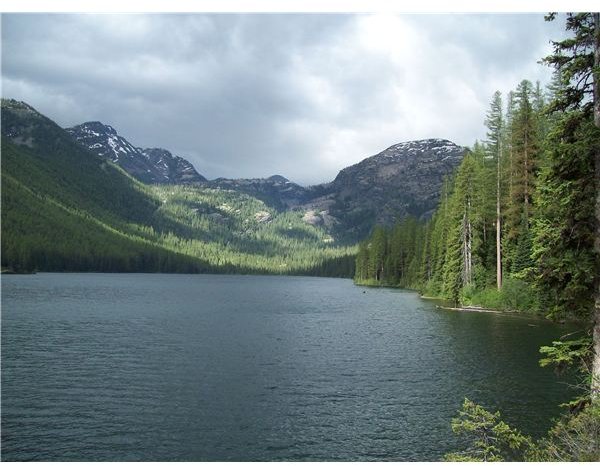

Image courtesy of commons.wikimedia.org

Typical Patterns in the Northwest

Normal weather patterns of the northwest region are marked by a great deal of precipitation (rain and snow) west of the Cascade Mountains while the eastern side of the range is considerably more arid. On average, the western side receives 12 more inches of rain than the eastern. In fact, in the summer, parts of eastern Washington and Oregon experience desert-like conditions, which make drought a constant problem for agriculture.

However, in winter, the prevailing winds coming down from the mountains make the temperatures in eastern Washington and Oregon colder. On occasion during the winter, warm blasts of winds, which are known as the Chinkook winds, come down on the eastern slopes of the Cascades. Much of the information we now have about climate and weather can be attributed to the series of research satellites dispatched and monitored by NASA and the USGS. Read about the amazing capabilities and intriguing findings of the latest edition in The NASA Landsat Program and the Legacy of Landsat 7.

The coastal geography of the most western portion of the Northwest creates a temperate zone because the Pacific is a stabilizing force that prohibits extreme temperatures. High humidity near the coast is also the result of marine influences. In addition, the typically warm Japanese current also contributes to this region’s milder climate. The whole Pacific Northwest Region receives more precipitation in winter. The prevailing Westerlies (common to all latitudes between 30 and 60 degrees) are blocked by the tall Olympic Mountains, which in turn creates all that rain Seattle is famous for; the technical term for it is orographic precipitation. The high peaks such as Mt. Hood and Mt. Rainier receive enough snow to vie for world records, and their peaks remain white throughout the year.

Rather than having four well delineated seasons, the Pacific Northwest is prone to two major seasons; wet and dry. Winter is dominated by a powerful low pressure channel coming from the Gulf of Alaska. Air generally circulates counterclockwise in a low pressure system meaning that the warm ocean wave producing Westerlies emanating from Hawaii will be picked up and driven in from the southwest, which also contributes to the mild temperatures along the coast known as the Pineapple Express.

Warm air holds more moisture than cold air, and we’ve already pointed out the extremely moist result. When this warm air rises and is cooled by the lower temperatures higher in the atmosphere, the Pacific Northwest is anointed with more precipitation than anywhere else on the North American continent.

Eighty percent of the precipitation falls between October and April. Between September and July, a high pressure system from the California and Oregon Coast takes root and pushes off those moisture-bearing clouds. The clockwise pattern of high pressure systems doesn’t hold the water, and they pick up and deliver air masses from the arctic resulting in cool and dry summer winds.

If you’d like to see trends over the last century, NOAA, particularly on their Northwest Fisheries Science Center website, has all the data you could want about it. What’s known as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) is a climate index incorporating factors such as sea surface temperature data, sea level pressure, winter land–surface temperature, precipitation, and stream flow. Much of this data goes all the way back to 1900. Check it out on the nwfsc.noaa.gov website because the scientists there explain it far better than this does. So there you have it, your typical and normal weather patterns of the Northwest region. If you’ve never been there, don’t let the weather hold you back, it has areas of gorgeous and lush forests and high desert scenery all split up nicely by awe inspiring mountains.

Image courtesy of the author

Sources

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: https://www.noaanews.noaa.gov/stories2010/20101021_winteroutlook.html