Introduction to View Camera Photography

What is a View Camera?

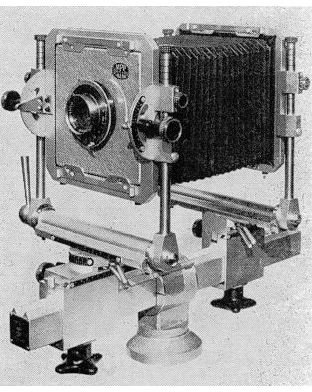

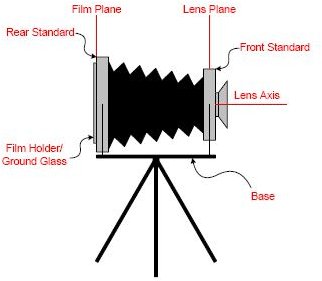

A view camera, also known as a large-format camera, looks just like those old-fashioned cameras where the photographer has to duck under a black cloth to set up the shot. The typical view camera has a lens board that holds the lens on the front and a ground-glass focusing screen on the back, with an accordion of light-tight fabric, leather or vinyl in between. There are no mirrors in a view camera; light passes directly through the lens to the ground glass, where the image appears flipped left-to-right and upside down. Once the image is composed, a film holder for sheet film is fitted into place, or a digital back is mounted, to capture the exposure.

View cameras are commonly seen in two varieties: monorail and field cameras. A monorail camera has the front and rear standards (the parts that hold the lens board and the focusing screen) mounted on a single rail, on which they can be moved backwards and forwards for focusing. A field camera (also called a baseboard camera or technical camera) is built like a box with a front that folds open to become the baseboard on which the lens board can be moved back and forth.

What are Camera Movements?

One of the most useful features of a view camera is the ability to move the front and rear standards independently. Camera movements can be used to correct a number of problems with focusing, by changing the plane of focus, and with perspective, such as correcting for keystoning and converging parallels.

Each type of movement has a different name. Rise and fall (sometimes also called drop) refer to the movement of the standards up and down, so “front rise,” for example, means moving the front standard up from its normal position. Tilt is the movement from the usual vertical position, and can be either up (tilting so the front of the standard is angled up) or down (angling the front down). Shift (also called cross) keeps the standard perpendicular to the rail, but moves it in a left or right direction, while swing rotates the standard from the perpendicular, also to the left or right (in relation to the front of the standard).

Monorail cameras have the most possible movements and the greatest range of movements. Field cameras generally have more front movement than rear movement, due to their construction. Some movements are also possible with smaller format cameras by using an attachable bellows between the camera and lens, or by fitting the camera with a tilt-shift lens. These are usually not nearly as flexible as a large-format camera, however.

Why Shoot Large Format?

The main advantage of using a view camera is the ability to use movements to correct various problems–mainly to do with perspective and focus, as mentioned above. These abilities are especially useful in architectural photography, but can also prove advantageous when photographing smaller subjects.

Another nice thing about large format, especially if you are working in film, is the ability to enlarge. While you can certainly enlarge smaller films, the more you do, the more you will lose sharpness. With a larger negative–large format film starts at 4 by 5 inches and goes up from there (the camera size matches the film size)–you’ve already got a larger image, so you can go quite huge before any visible loss of detail occurs.

You can get digital backs for large format cameras, but they are extremely expensive and so are beyond the reach of any but the most serious photographer. Used analog view cameras can be had for reasonable prices, however (generally the better the quality, the higher the price, but a decent view camera can be purchased on the secondary market for a few hundred dollars). View cameras can be a good basis for developing a film-digital hybrid way of working, such as shooting film then scanning and processing digitally to make prints.

Through-the-Viewfinder With a View Camera

Another form of analog-digital hybrid photography is through-the-viewfinder photography or TTV. TTV photography is most commonly done with medium-format cameras that have waist-level viewfinders, and it captures the (often old-fashioned) look of the film camera in a digital format. TTV can be done with nearly any analog camera, though, and using a view camera coupled with your digital camera will give the advantages of the view camera plus the advantages of digital images.

Essentially, through-the-viewfinder photography uses an analog camera as a sort of lens filter. A second camera–most often a digital SLR–is rigged up to shoot through the other camera’s viewfinder. TTV photography requires some basic DIY ability, as you have to construct a means of connecting the two cameras and blocking out extraneous light. It can be cumbersome, especially if you end up having to connect two cameras on tripods, but it’s not that much more difficult than setting up a view camera by itself, and it can result in images that may make it well worth the bother.

References

- Dorrell, Peter G. Photography in Archaeology and Conservation. Second edition. Cambridge UP, 1994.

- Image 2 Credit: View Camera by Chris Heald [CC-BY-SA-3.0 or GFDL] via Wikimedia Commons.

- Image 1 Credit: Chambre photographique monorail MPP (1968) by Jean-Jacques Milan [CC BY-SA 3.0 or GFDL] via Wikimedia Commons.

- Upton, Barbara London, with John Upton. Photography Fourth edition. Scott, Foresman and Company, 1989.

- White, Robert. Discovering Old Cameras 1839-1939. Third edition. Shire Publications, 1995.

- Horenstein, Henry. Black & White Photography: A Basic Manual. Third revised edition. Little, Brown and Company, 2005.

- Image 3 Credit: Set-up for through the viewfinder photography by Seriykotik. Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.