Security Concern in UAC in Windows 7 - Not a Vulnerability Says Microsoft - Many Disagreee

Introduction

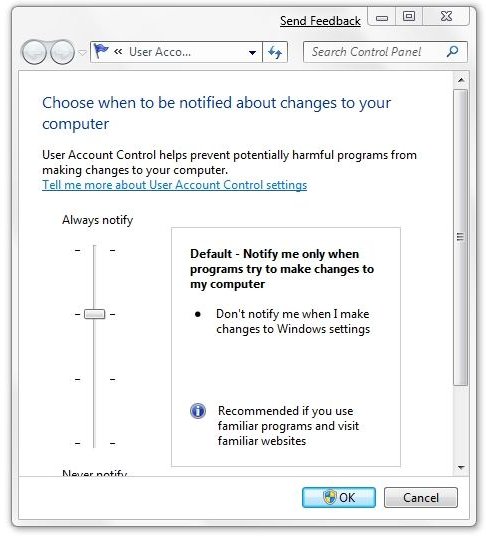

Recently, a controversy has arisen over how UAC, or User Access Control is implemented in the Windows 7 beta version. Before getting into the details, here are some basics to consider. (Hover over the image to read the label, or click the image to enlarge.)

When set at this default level, UAC will “Notify me only when programs try to make changes to my computer.” Furthermore, “Don’t notify me when I make changes to Windows settings.”

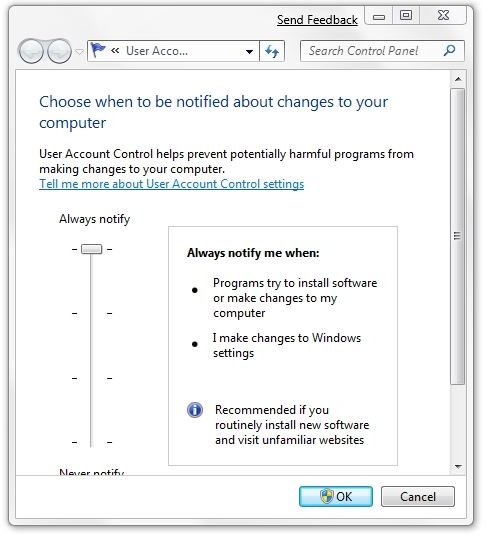

Now compare that to the maximum “Always notify” setting. At this level, Windows will always notify the user when “Programs try to install software or make changes to my computer” or when “I make changes to Windows settings.”

Now let’s try an experiment. Let’s click OK to select the maximum settings and close the dialog. Then reopen it by typing “UAC” into the “Search programs and files” field in the Start menu and select “Change User Account Control settings.”

That will place us back at the same dialog with the maximum warning level selected. Now we drag the slider back down to the default level and click OK.

A UAC prompt and the screen dimming into Secure Desktop Mode occurs before the new setting is accepted. This is completely expected because we told it to warn us before we make changes to Windows settings.

This is how it’s supposed to work.

The Problem

Now let’s look back at some of the recent developments involving UAC in the Windows 7 beta. On January 30th, Rafael Rivera, in his “Within Windows” blog posted “Malware can turn off UAC in Windows 7; ‘By design’ says Microsoft.” Also on January 30th, Long Zheng, in his “I started something” blog posted “Sacrificing Security for Usability: UAC security flaw in Windows 7 beta (with proof of concept code).”

Zheng writes that with the “help of my developer side-kick” Rivera, they were able to come up with a “fully functional proof-of-concept in VBScript” that could emulate a few keystrokes and change the UAC security level without a UAC prompt. If then, Zheng proposed, the malware doing this installed a malicious program, wrote itself into the Windows Startup folder, and demanded a restart, it would then be free to “run with full administrative privileges ready to wreak havoc.”

So, does a real problem exist here? Yes. The user would still have to somehow activate the malicious program before it could act, but if it were a trojan pretending to do or be something else, the damage could certainly be done with the user remaining blissfully unaware.

In an update, Zheng noted that for this particular vulnerability to work, the user would have to be a member of the “Administrative” group rather than the “Standard” group. Since nearly 75% of Vista computers, according to Microsoft, are operated by an owner “who is the PC’s administrator and sole user account,” the vulnerability could be widespread.

My Background

In my own experience, I can compare the way UAC works in Windows to the way privileges work in Unix-like environments such as Linux.

Redhat Linux, which I ran years ago, had two levels. Running as a common user, I could change all the settings that applied to my personal “space.” To make broader changes, I could enter a password and become the “super user” temporarily to carry out certain tasks that could make system-wide changes. I could also log in as the root, or super user, and have total control over the system. This was broadly considered unwise by the user community and was referred to as “rooting around.” Also, once I became the super user, I remained the super user until the session ended.

A different, questionably better, but more modern solution is found in Ubuntu Linux. In it, I also normally run as a common user. If I need to make a change to a system-wide setting, I can enter the USER password and temporarily elevate my user privilege, but only as long as needed to accomplish the specific task. This temporary elevation also shortly times out. Actually, there is a secret root user in Ubuntu, but since I run a single user machine, I don’t even need to know that account’s password (and I really don’t).

So Vista’s and Windows 7’s approach is somewhat like Ubuntu’s. In Vista, every change in Windows settings required a confirmation, which is similar to an elevation in privileges. In Windows 7, the prompting level is user adjustable. And in each case – Redhat Linux, Ubuntu Linux, Vista, and Windows 7 – some elevation of privilege is needed to make changes that affect the entire computer.

Next: Elevated Privileges, Microsoft’s Response, and our Summary

The problem in Windows 7 is that a malicious program does not have to run with elevated privileges to change the UAC prompting level. That’s right. The program that Rivera and Zheng created runs at a standard user privilege level.

The cure seems to be simple: redesign UAC slightly so that any decrease in UAC always requires a user prompt and a flip to the Secure Desktop Mode. The user should then certainly realize that something is going on that he did not intend.

Microsoft’s Response

As related by Paul Thurrot in his “Supersite [for Windows] Blog,” Microsoft claims that the issue is “not a vulnerability.”

Specifically, and quoting from Thurrot’s post,

- This is not a vulnerability. The intent of the default configuration of UAC is that users don’t get prompted when making changes to Windows settings. This includes changing the UAC prompting level.

- The only way this could be changed without the user’s knowledge is by malicious code already running on the box.

- In order for malicious code to have gotten on to the box, something else has already been breached (or the user has explicitly consented).

Thurrot did not specify who at Microsoft had sent him that, but he ended the post by saying, “There you go.”

By design. I don’t doubt it.

Summary

There are no perfect solutions in security. I asked an associate who is in IT administration what level of control he would want if his company ever decided to deploy Windows 7 to the company desktops. To my surprise, he told me that he’d want a team of three persons. One would be a network specialist for communications and Cisco/Novell permissions. Another would be for server build architecture and access to departmental systems. And the third person would be a “spare to cascade down in case the second person wasn’t available.” This person would also be responsible for “interface engines and messaging.”

Seen in that light, the controversy over non-privileged applications being able to access and change UAC in Windows 7 somewhat pales. For the rest of us, however, it looks like a security hole that Microsoft should fill.

Maybe there’s more to this story. Maybe there’s a reason that Microsoft doesn’t want to change the design at this late date. Maybe there are technical reasons why it’s unfeasible or undesirable.

But the cat is out of the bag now. Whether Microsoft chooses to call it a vulnerability or not, malware authors have taken note.

As I mentioned previously, the fix could be as simple as requiring that any change to the UAC level, particularly any downward change, be met with a full UAC prompt with Secure Desktop Mode dimming.

I suspect that we have not heard the last of this story. It’ll be interesting to see if Microsoft holds the line or capitulates.