Industrial Cyberwarfare: What Businesses are Most at Risk?

The Beginnings of Industrial Cyberwarfare

There was a time when all a business had to be concerned about was taxes and keeping their trade secrets locked up, safely out of the hands of overseas competitors or perhaps the Eastern Bloc.

With the proliferation of online access, however, has come a new threat. That sort of industrial espionage is now a thing of the past; the real threat to companies in North America and Europe isn’t from communists or competitors, but from acts of cyberwarfare, usually originating in Asia or Russia.

While the technology has been available for 40 or so years it is only since the mid-1990s that the use of the Internet has made such attacks possible, and only since 2000 when the states considered responsible began rolling out access to online services.

One thing that needs to be made clear about cyberwarfare is that no one is ever responsible. Whomever is blamed can safely issue a denial because it is comparatively easy for the perpetrators to hide their actions online. As a result, the focus in anti-cyberwarfare activities seems to be protection, avoidance and retaliation, rather than blame.

The Impact of Stuxnet

Cyberwarfare has been quietly waged across the Internet in earnest since the mid 2000s, with the discovery of botnets, vast networks of computers enslaved by malicious software (often installed via Trojans) that are then used to drive a particular website offline with a Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attack.

Browser vulnerabilities aside, the majority of cyber attacks in the 2000s were of the botnet variety until the latter half of the decade. At this point things started to get more serious. An Indian bank was hacked by a group from Pakistan; the Pentagon was hacked by computers based in Russian; intellectual property was stolen in a zero-day vulnerability attack (thanks to a weakness in Internet Explorer 6); most embarrassingly, US army drones were compromised by Afgan insurgents using $26 software from Russia.

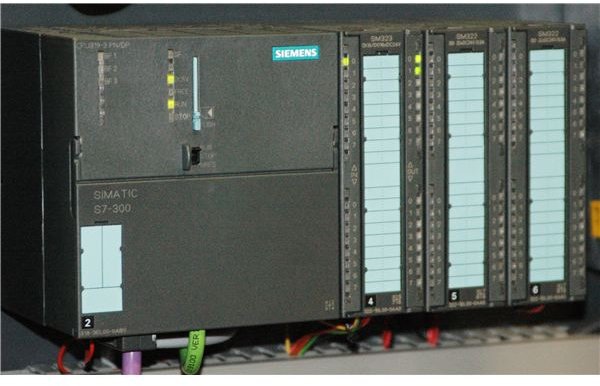

But none of these examples is as devastating as Stuxnet, the mysterious worm thought by many online security specialists to have been a collaboration between the USA and Israel. Discovered in June 2010, the malware was designed to specifically target Windows-based industrial software designed by Siemens. Such computers can often be found involved in the process of uranium enrichment, a process involved with the development of nuclear technology, so it should come as no surprise to learn that Symantec reported that 60% of computers with Stuxnet infections were found in Iran.

Theoretically designed to throw Iran’s nuclear project into disarray, Stuxnet has been responsible not just for causing problems in Iran but for raising awareness of such threats.

Whether national governments were involved in Stuxnet or not, the modus operandi of the software - to damage processes and send vital data to a remote location - is that of an industrial cyberwarfare attack.

Is Your Business Next?

Judging whether your business could be at risk from cyberwarfare largely depends on assessing exactly what your organization does, and whether it offers any particular service that cannot be found elsewhere.

For instance, if you head a charitable organization, the chances are that you won’t be targeted by cyberwarfare (although if you support a particularly contentious issue, there may be some unwelcome attention). On the other hand, if your company is a Department of Defence contractor then there is naturally a risk of cyberwarfare.

In order to judge the likelihood of an attack you will need to establish your place in the grand scheme of things. If your company provides fibre optic cables to the communications industry then there may be a chance of an attack on you as part of a wider strategy. Should you provide payroll services for a small clothing shop in the next town, however, then you are probably safe.

As each business has a role in the day-to-day running of its country, it should be easy to ascertain whether or not you are likely to be attacked in this way. If you don’t have any online operations then you can consider yourself relatively safe; if your business doesn’t use computers then of course you are completely safe, although people who you do business with, or your bank, may not be.

Ultimately, an industrial cyberwarfare attack can have repercussions beyond the targeted business, so steps should be taken to protect your systems. In the case of Stuxnet, Symantec issued protection in the shape of virus definitions to remove the worm on systems protected by their software.

What Can Be Gained from an Industrial Cyberwarfare Attack?

As with any sort of attack, the aim of an industrial cyberwarfare attack is to gain an advantage.

Whether this advantage is acquired by theft or damage or both, the victim is likely to come off worse without an operational disaster recovery program, especially with the DuQu virus currently doing the rounds.

Apparently derived from Stuxnet and so named because of the .dq file extension that it assigns the files that it creates, DuQu follows in the footsteps of its older brother by targeting industrial control systems in factories and power plants, gathering data and forwarding it to a remote location.

In the physical world this would be tantamount to infiltrating a large company, destroying its production line and stealing a few filing cabinets.

There are many ways in which such an attack might prove useful in open warfare, such as setting back the enemy’s weapons production, but in a purely industrial context, the real advantage is monetary.

The prospect of being able to get one over on your competitors is an obvious attraction, and those that engage in industrial cyberwarfare on any scale have always got one eye on the profit margins. With patents and other intellectual property potentially available for viewing following such an attack, it should come as no surprise to learn that unscrupulous businessmen will consider anything to gain an advantage.

Industrial Cyberwarfare: The Future

As things stand, DuQu - the virus first described as “Son of Stuxnet” - is the pinnacle of industrial cyberwarfare software development.

However as more and more government departments and jobs are shipped out to private contractors it can only be a matter of time before the use of such tactics becomes much more widespread, with attacks launched by both home-grown and foreign businesses and governments.

One of the disadvantages of globalization is that everyone is a competitor, which means gaining a foothold into new territories (such as the developing markets of Asia and South America) is vital. For one company to have an advantage here the use of industrial cyberwarfare might be considered.

However there are still plenty of reasons to be confident that such attacks might be restricted in the near future. Legal experts of the various companies around the world affected by Stuxnet and those representing Siemens are yet to make decisions on what action they will take against the people behind Stuxnet, whoever they are…

References

- Image credit: Wikimedia Commons/Palatinatian

- Ackermann, Ernest. “Industrial Cyberwarfare – Stuxnet, Duqu, what’s next?”, http://blogs.fredericksburg.com/ackermann/2011/10/24/industrial-cyberwarfare-stuxnet-duqu-whats-next/

- The History of Cyber Warfare, http://online.lewisu.edu/the-history-of-cyber-warfare.asp