Intel's First 32nm CPU - The 2 Core Clarkdale Westmere with Integrated Graphics is a Nehalem for the Mainstream

Intel Replaces Havendale with 32nm Clarkdale

Intel is keen to bring its 32nm CPUs to market, despite the weakness of the economy. In order to do this, they have delayed and replaced the first proposed 2 core Nehalems, Havendale (desktop) and Auburndale (laptop), with 32nm versions called Clarkdale and Arrandale, due by year’s end. It is possible they will be marketed as Core i3 or Core i4.

The first mainstream Nehalems, 45nm, 4 core, called Lynnfield and Clarksfield, are due in Q3, likely under Core i5 branding. A new Core i7, codenamed Gulftown, at 32nm with 6 cores, is in the works for release early next year. The mobile Arrandale will be discussed in another article soon.

This article deals with the desktop Clarkdale processor.

Meet Intel’s Clarkdale, the World’s First 32nm CPU

Clarkdale will be a 2 core, Nehalem microarchitecture CPU - the first to be made on a 32nm process. Like the rest of the Nehalem family, Clarkdale uses Hyper Threading, which allows each core to handle two threads. The cache design also appears to be the same, at least on a per core basis, giving the Clarkdale 4MB of shared L3 cache.

It also has an integrated, DDR 3, memory controller as does the rest of the Core iX branded chips. The Core i7 has a triple channel controller, though, while Clarkdale (and Lynnfield) are dual channel. It also brings the graphics controller onto the CPU (like Core i5, but not Core i7). Even the integrated graphics are brought onto the processor in the Clarkdale, about which Intel is pretty excited, though the silver cloud definitely has a grey lining. More on Intel’s graphics on the CPU later.

Further differentiating it from other Nehalems, Clarkdale will use its own socket, LGA 1155. We knew before Core i7 launched that later, and lesser, Nehalems would use a different socket than the X58’s LGA 1336. Now, we have learned that upcoming 2 and 4 core Nehalems will require different sockets: LGA 1156 for Lynnfield; LGA 1155 for Clarkdale.

Ibex Peak: No More Northbridge

With the memory and PCI-e controllers on the CPU itself, and even integrated graphics in the Clarkdale’s case, the Clarkdale and Lynnfield processors perform most of the functions traditionally assigned to the northbridge. As a result, the Ibex Peak platform those CPUs use, (which will come to market as Series 5), does not have one.

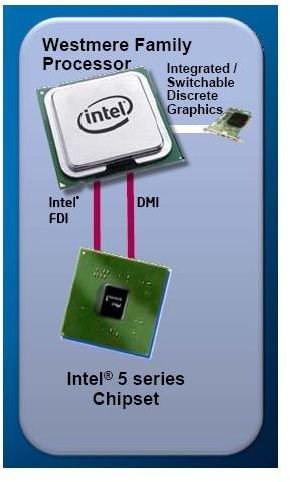

Because the Ibex Peak platform has the graphics speaking directly to, or even on the CPU itself, it only needs to handle CPU communication to the southbridge (which is now essentially the whole chipset). As this connection doesn’t need as much bandwidth as it would if it carried graphics the way it does on the Core i7/X58, the Ibex Peak platform uses Direct Media Interface (DMI). This is instead of the Quick Path Interconnect on the X58 (Tylersburg) platform.

Intel’s DMI is currently used to connect the north and southbridges at 2 GB/s, on both the Nehalem Core i7/X58, and Core 2/Series 4 chipset. Because the Clarkdale has onboard graphics, it needs a way to get these to the display output. A second connection between the CPU and southbridge, which Intel calls Flexible Display Interface, does this.

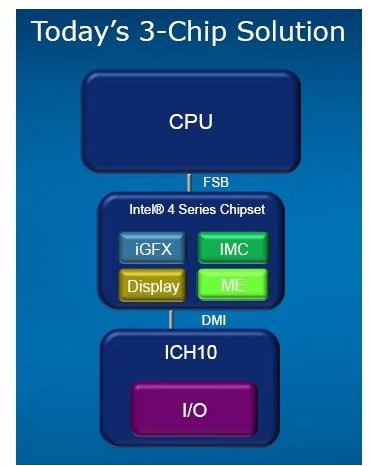

Intel Platform Comparison: Core 2 Series 4, Nehalem X58 Core i7, Nehalem Series 5 Ibex Peak for Clarkdale

The diagrams above show, from left to right: a traditional Series 4 platform, with FSB connecting CPU and northbridge, and DMI connecting northbridge and southbridge; a Core i7/X58 or Tylersburg setup, with QPI connecting CPU to northbridge, and DMI connecting north and southbridge; finally, a Series 5 or Ibex Peak platform for Clarkdale, with no northbridge, and DMI and FDI connecting the CPU and southbridge directly.

On the next page, performance and prices.

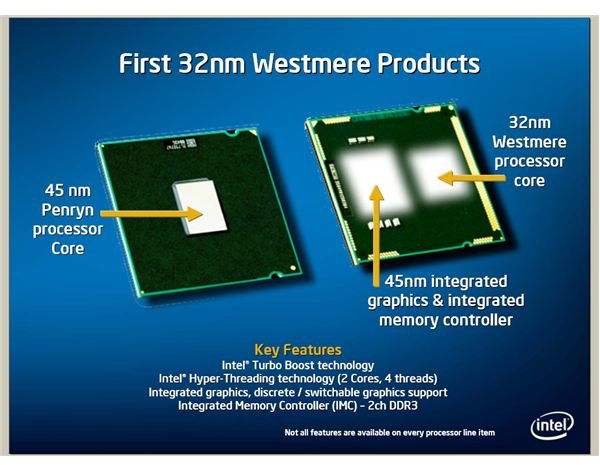

Little Chip, Big Graphics: Process Size Wise, Anyway

It’s worth noting that while the processor part of the Clarkdale chip is 32nm, the controllers previously found in the northbridge and the integrated graphics now on the CPU are still built using a 45nm process. This makes sense, since Intel can reserve its 32nm manufacturing capacity for the chips, and supporting elements can come off its extremely reliable 45nm lines. We can see from the image on the right that the 45nm section takes up more space than the 32nm one.

The second image puts the size difference in perspective. It also shows that Intel VP Steve Smith isn’t wasting any time or money at the spa in this rough economy. Clearly, and thankfully, he is more worried about shrinking chip manufacturing processes than waxing those impressive eyebrows.

Nehalem Clarkdale: Performance and Price

Obviously, any information we turn up this far out will be scant and subject to change. However, Fudzilla has posted some interesting numbers. They are reporting there will be 3 varieties of Clarkdale. Taking into account the difference between retail and wholesale prices, we should see: an entry level chip for about a hundred dollars, meant to replace the E5400, the latter having a 2.7GHz clock; a midrange chip for about $125, replacing the 2.8 GHz E7400; and one for about $150 that replaces the 2.93 GHz E7500.

If we assume similar clocks to the parts they are replacing, the benefits will all be on the power use (due to the process shrink) and clock for clock sides. Provided we see similar improvements in clock for clock performance to what the Core i7 Nehalems brought to the table, that’s nothing to sneeze at. Particularly since the new Clarkfield chips seem to be priced right in line with their replacement targets, and include on chip graphics.

Of course, prices on the currently available chips are likely to fall. Then again, Intel might succumb to economic pressure and lower the new chips launch price as well. In all, that isn’t the biggest threat to Clarkfield’s success.

Dated Graphics and Limited Platform Flexibility Hamper Clarkfield

As mentioned earlier, Clarksfield will appear on its own socket, LGA 1155, as opposed to using either of the other two Nehalem sockets. The roadmaps also indicate that Clarkfield CPUs will be the only to use the LGA 1155 socket until Intel decides to come up with more chips. Lynnfield will use socket LGA 1156, and the next Core i7 appears to continue with the LGA 1336.

That means you can’t combine integrated graphics with a quad core, and that using a dual core with dedicated graphics means paying for integrated graphics you don’t need. Worse still, you can’t build on a budget now, and upgrade the CPU later. You can add dedicated graphics, but a move to a CPU with more cores means a whole new motherboard.

The lack of flexibility is only one issue. The second is that the graphics on the CPU, despite graphics on a CPU being quite a feat on its own, aren’t that hot. Actually, they are a warmed over GMA 4500 that Intel has had around for a while. We talk about the CPU integrated graphics here.

What to Do?

Indeed, upgrading to Nehalem seems like it will be fraught with peril. The Clarkfield option seems aimed at OEM system builders. Since the CPUs appear to include northbridge and graphics for little cost over their replacement target CPUs, and an Ibex Peak motherboard doesn’t need these parts, the cost of such a platform could be kept quite low.

OEM’s might get excited about a cheaper way to build a PC that can surf the web and, if you close all the other apps on the system down, play movies. People who pay more attention to their hardware selections are unlikely to choose Clarkfield as, for the time being, the graphics are too old and the platform is too inflexible to be attractive.

Users are more likely to stick with LGA 775 or pick another (more expensive) Nehalem socket option, even move to AMD. We further discuss the difficulty in upgrading to Nehalem here.