What is Soil Made Of? Learn the Components of Soil

What is Soil Made Of?

At its broadest, the term soil can refer to any kind of loose sediment. In geology, soil is the end result of rock weathering. And in soil science, it is weathered rock combined with decayed organic material that can support plant growth.

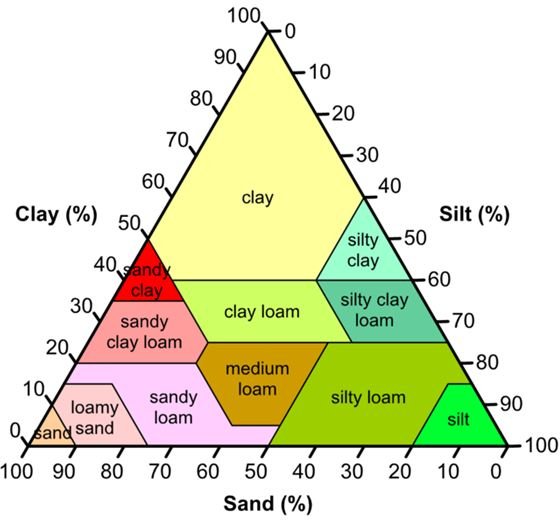

Soil is made of sand, silt, clay, and humus (decayed organic material). How much of each is in the soil depends on the type of rock it weathered from, how long weathering has been occurring, the local climate (wet or dry, hot or cold), the abundance of plant life to decay into organics, and the ecosystem of living things that decomposes the dead plants.

Sand is important for keeping the soil loose, aerated, and well-drained. Clay minerals hold water and nutrients in the soil just loosely enough to allow plant roots to take them. And humus provides the bulk of the soil’s fertility.

What Soil is Made Of: Sand, Silt, and Clay

It begins with solid rock. For soil-forming purposes, rocks come in two broad categories, silicate and carbonate, and are subject to two types of weathering, mechanical and chemical.

Mechanical weathering does the same thing to all rocks: breaks them down into small pieces, which eventually become the size of sand, silt, and clay. Sand, silt, and clay are primarily measures of grain size. Sand grains have a diameter from 1/16th to 2 mm. Silt is between 1/256th and 1/16th mm, and clay is anything less than 1/256th mm. Sand looks like individual grains and feels gritty to the fingers. Silt looks like flour and feels gritty between the teeth. And clay isn’t gritty at all.

Beyond grain size, sand and clay typically have very different chemical compositions, especially after long-term weathering - to the point where the minerals making up the end result clay-sized particles are called clay minerals.

Chemical weathering does very different things to carbonate vs. silicate rocks. Carbonate rocks, such as limestone and marble, are composed mainly of the mineral calcite. Calcite completely dissolves under chemical weathering, eventually leaving nothing solid behind. In the context of soil, carbonate rocks are a natural source of lime.

Chemical Weathering of Silicate Rocks

Silicate rocks include all types of igneous rocks (the most common are granite and basalt), sandstone, shale, and most types of metamorphic rocks (slate, phyllite, schist, and gneiss). For soil-forming purposes, they are made of two types of minerals: quartz and everything else.

Quartz, or SiO2, has a very sturdy 3D tetrahedral framework structure that isn’t affected at all by chemical weathering. Through mechanical weathering, quartz eventually becomes sand. After long-term weathering, all of the sand in the soil will be quartz.

Silicate rocks that are basically all quartz, like sandstone and metamorphic quartzite, will only produce sand. Silicate rocks that don’t have any quartz at all, such as mafic igneous rocks (basalt), might not produce any sand. In between, how sandy the soil is depends on how much quartz the rock has and how long weathering has gone on to break down non-quartz sand-sized particles.

Everything else includes the ferromagnesian minerals (olivine, augite, hornblende, and biotite), garnet, feldspars, and micas. They have a variety of crystalline structures, from single and double chains of tetrahedrons, to 3D frameworks similar to quartz, to sheets. Early in the development of a soil, some of these will be sand-sized particles, especially feldspar. Under chemical weathering in the long-term, all of these become clay minerals (kaolinite, montmorillonite, talc, and many others), which have a sheet structure that occur as tiny flakes.

Clay minerals have a negative electrical charge on the flat parts of the flakes. This allows them to attract and hold water molecules and positive ions like Ca++ and K+, which are important plant nutrients.

What Soil is Made Of: Sand, Silt, and Clay (continued)

The sand, silt, and clay that results from rock weathering form the basic components of soil. If the material stays where it formed - above or otherwise in contact with the unweathered parent rock - the soil is called a residual soil.

Soil can also be eroded away from the parent rock by wind, water flow, or glaciers, and deposited far from where it originally formed. Those soils are called transported soils. The soils of river floodplains and deltas are transported soils. Loess is a soil from windblown deposits. Transported soils are generally not related to the local bedrock.

What Soil is Made Of: Humus

After a plant dies, things living in the soil such as earthworms, fungi, and soil microbes decompose it by eating its constituent organic compounds - carbohydrates, proteins, fats, lignins, etc. The end result is a stable, dark-colored organic material called humus that doesn’t decompose further and can remain unchanged for centuries.

Humus is also called compost when produced by composting. A soil made of mostly organics (that may or may not have reached the humus endpoint) with little sand or clay is called peat or muck.

Soil Structure: Horizons of a Soil Profile

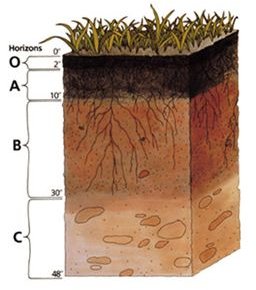

As soil develops, it forms layers. The layered structure is called a soil profile, and each layer is a soil horizon.

The top layer, called the O horizon, is a thin layer of mostly dead plant matter. Under it is a layer rich in humus and minerals, called the A horizon. The A and O horizons together are also called topsoil.

Under the topsoil, there is often a zone of leaching. As rainwater percolates through the soil, it washes down material from the layers above - dissolved calcite, iron oxides (gives soil color), clay minerals, products of humus decay - leaving behind pale sandy material. In the most simplified diagrams, this is often called the A horizon (and the topsoil layer is the O horizon); in more detailed schemes it’s the E horizon.

The B horizon is where all the stuff leached from above ends up. Also called the zone of accumulation, it’s a place that tends to be clayey and stained red with iron oxides. It’s a place where clays can compact to the point of making a layer impermeable to water, called hardpan, and where calcium carbonate can precipitate back out to glue soil particles together in a type of hardpan called caliche. Acids and salts can also accumulate in the B horizon, which reduce plant growth.

The C horizon is a zone filled with large chunks of parent rock in the process of weathering. This zone is just above the R horizon, or bedrock.

References and Image Credits

Plummer, Charles C. and David McGeary. Physical Geology 5th ed. Wm. C. Brown Publishers. 1991.

Keller, Edward A. Environmental Geology 6th ed. Macmillan Publishing Company. 1992.

Soil Types by Composition triangle by Richard Wheeler, used under CC-A-SA 3.0 license.

Soil Horizons picture by USDA, public domain.

This post is part of the series: The Processes of Weathering in Geology

Rocks at the Earth’s surface break down over time through weathering. Mechanical weathering breaks them into smaller pieces with physical forces, while chemical weathering transforms their constituent minerals into different chemical forms. The end result is called soil. Learn the details here.