The Purpose of a Ring Flash in Photography

What is It?

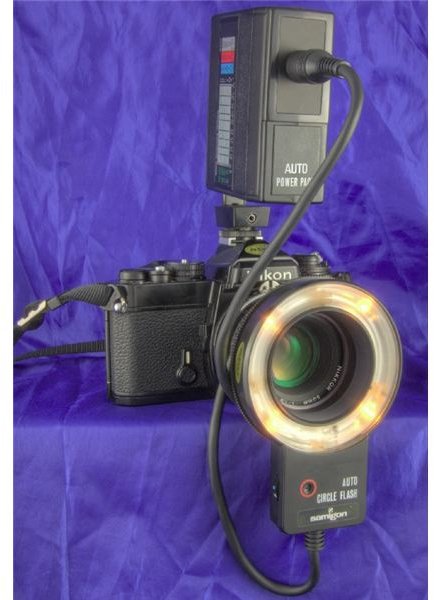

A ring flash, as its name indicates, is a ring-shaped flash unit. It is intended to fit in a circle around the camera lens with the light originating on the same plane as the lens’ optical axis. The typical ring flash mounts on the camera lens, with a cable leading to a second section that mounts on the hot shoe to power the flash.

Some larger ring flashes, such as those used in fashion photography, have a separate battery pack or AC adapter to power them, so as not to drain the camera’s battery. A few have battery packs contained right in the same unit as the bulbs, and one type of lens developed for medical photography even has the ring lighting built into the lens, but these are less common than flashes with hot shoe connectors or battery packs.

Within the flash unit, there may be one or more bulbs. Where there are multiple bulbs, they are often individually controllable to achieve different effects. This is particularly useful on low-relief objects where 360-degree lighting would completely flatten the features, but three-quarter lighting would allow the relief to show.

What is It Used For?

The ring flash was invented in the 1950s by a dentist named Lester Dine. It was intended for use in dental photography, where conventional flash can create obscuring shadows. Because the ring flash produces a near-shadowless diffused light, it was perfect for close-ups of teeth. A ring flash is also used in other types of medical photography where even lighting of up-close subjects is required.

These same qualities make a ring flash especially good for macro photography, where the camera is too close to the subject for most other types of flash to produce satisfactory results. A ring flash is especially useful for subjects such as insects which need to be photographed in the field–the circular, diffuse light can create a lighting effect very much like that produced by a soft box. Because the flash is mounted on the lens and doesn’t have to be set up separately, it’s a convenient way to add enough light to allow smaller lens apertures for maximum depth of field, which is always a problem in extreme close-up situations.

Particularly shiny objects, however, may create too much reflection for a ring flash to produce good results, and very flat relief may be lost unless the flash has separate bulbs that can be switched off to create somewhat more directional lighting.

Fashion and portrait photographers have also begun to use ring flashes in recent years. The circular light creates an attractive shadowy halo on the subject and acts as a fill light to soften shadows when used as a secondary light source. A ring flash is well-suited as a fill light for portraits because it does not produce shadows of its own. This kind of flash does not work well with large groups, however, as the flash isn’t strong enough to light multiple subjects from farther away.

Should I Buy One?

If you’re doing a lot of macro photography in the field, or are shooting a lot of relatively close-up portraits or fashion images, then a ring flash can be a good investment. They don’t come cheap, however, so make sure you really need one before buying unless you have money to burn.

One way to see how much you’d use a ring flash, or if you even like the lighting effect it gives your particular photographic style, is to try before buying. If you have a photographic rental shop nearby, you can rent one, or you can also get an attachment for a normal shoe-mounted flash that (sort of) turns it into a ring flash by diffusing and bending the light around the lens. You can also try this DIY tutorial to create your own budget ring flash using a standard external flash unit and a couple of plastic bowls.

Craft and hobby stores also sell a kind of work lamp with a circular light surrounding a magnifying glass. If you take the glass out, you can use the lamp as a makeshift ring light, though obviously it’s not portable and would only be useful in a home studio where you can plug it into a wall socket. You may also find that a desk lamp doesn’t produce enough light for your purposes. Make sure to check what kind of bulb is used in the lamp and compensate with filters or camera settings, or remember to adjust the color balance in your photo editing software later as different bulb types will produce different color casts in the image.

Once you’ve tried a ring flash, either by renting a real one or constructing a makeshift unit, you’ll soon discover if you find yourself reaching for it all the time. Then you’ll know investing in one might be worth the money. If the makeshift one works well enough, though, you could spend the money on something else.

References

Adams, Ansel. Artificial Light Photography. New York Graphic Society, 1956.

Calder, Julian and John Garrett. The 35mm Photographer’s Handbook. Pan Books, 1979.

Dorrell, Peter G. Photography in Archaeology and Conservation. 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Horenstein, Henry. Black & White Photography: A Basic Manual. 3rd edition, revised. Little, Brown and Company, 2005.

Image: Ring Flash by Darron Birgenheier (Flickr) [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons.