How Does Linux Work - Understanding Linux Basics

Introduction

In many ways Linux is no different from any other operating system. It runs on the same computer, and the inner workings are the same as those that drive Windows, Linux, BSD, MacOS, etc. But there are fundamental and compounding differences from that point forward. Here we will cover how Linux works? Starting at power on, and finally reaching the desktop.

The Linux Boot Process

When you press the “On” button on your PC to start it, the computer wakes up the same way we do every morning. We open our eyes and check if there is anything wrong from the time we went to sleep. On a computer this is performed by the BIOS (Basic Input Output System) on the motherboard. The BIOS is the small chip that has the responsibility of identifying, checking and initializing system devices such as graphics cards, hard disks, etc.

To do this the BIOS makes a POST (Power On Self Test) and then checks which drive to use as the primary boot device. Normally this is set through the BIOS configuration screen and the first boot device can be identified as the CD-ROM, USB drive, hard disk or floppy disk. Let’s say that our system is configured to boot from CD-ROM and then Hard Disk. The BIOS checks the CD-ROM device to see if a CD/DVD resides there and is bootable. If so it boots from the CD-ROM, if not it turns to the hard disk, and hands over the control of the computer.

The boot of the operating system starts here, with the boot partition always located at the same place for all operating systems: track 0, head 0 and cylinder 0. Then the small program here, which is GRUB (GRand Unified Boot loader) or LILO (LInux LOader) performs the initialization and boot of the operating system, and since many distributions implement GRUB as their default bootloader, I will go with this one.

The GRUB is either in /boot/grub/menu.lst or /boot/boot/menu.lst. A sample GRUB configuration file is as follows:

==============================

default 0

timeout 5

Linux

root (hd0,0)

kernel /vmlinuz-2.6.22-bf2.4 root=/dev/sda0 ro

===============================

Now, the GRUB knows that the kernel version 2.6.22 is to be loaded and it is in root (/) directory (the kernel is a compressed file and can decompress itself in case of a system call.) GRUB makes a call to the kernel (which is the vmlinuz-2.6.22-bf.2.4 file in the configuration above) to decompress itself and start.

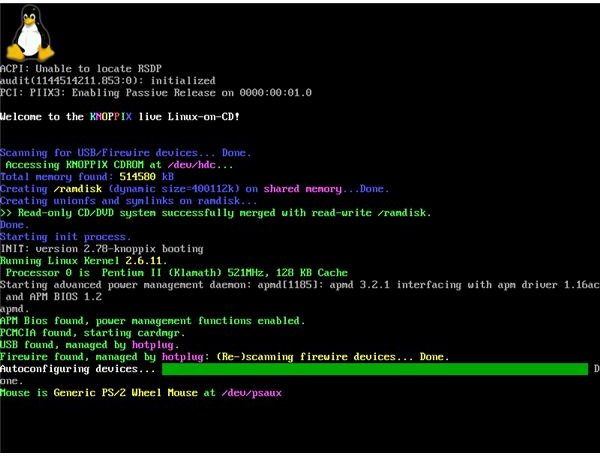

The kernel checks if your graphics card is there and running and if it supports complex text modes. After that it checks the hardware present on the computer (hard disks, network cards, TV cards etc.) and loads the relevant drivers. The kernel displays all the progress with informative messages during this time, as you can see in the screenshot.

After this boot stage the kernel tries to mount the file system. It tries to auto detect the file system and if it succeeds, carries on. If not, a kernel panic occurs and the system stops. If not, the kernel finally hands over the remaining job to the process named init and waits.

Init is the first process in the Linux system, with Process ID (PID) 1 and it initializes the rest of the system.

Linux Runlevels

Users migrating from Windows have difficulty understanding the runlevel concept in Linux. We have to understand what is a runlevel? And what does the computer do at the specified runlevel? to understand the remaining init process.

Linux is a multiuser system and it loads/halts the necessary programs to act as single user, multiuser, graphical desktop, and to halt or restart the system. The runlevels are numbered from 1 to 6 and the corresponding system states are as follows:

Runlevel 0: shutdown/halt the system

Runlevel 1: single user mode

Runlevel 2: multi user mode without network

Runlevel 3: multi user mode with network

Runlevel 4: reserved for local use (GUI mode for Slackware only)

Runlevel 5: graphical user interface (GUI) mode

Runlevel 6: reboot

There are programs that have to be started in each runlevel. These programs are listed in rcX.d files, where X indicates the runlevel number (for example rc3.d is the file that holds information about which programs to start/stop for runlevel 3.) /etc/init.d file holds the information to point at these files for the init to look for.

NEVER SET YOUR DEFAULT RUNLEVEL TO 0, 4 OR 6!

We said the programs are started or stopped. If the computer is booting, the programs are started and preceded with S in the rcX.d files. If the computer is shutting down, they are preceded with K. ‘S’ is for ‘start’ and ‘K’ is for ‘kill’.

Having all these in mind, let’s go on with the init process.

Init

When the init process starts, it checks configuration files to carry on its job. First of all, it looks at the /etc/inittab which tells the init which processes to start. In the /etc/inittab file is the information about the runlevels. The default runlevel for the system is indicated by the line id:X:initdefault where X is the runlevel number.

As you may have guessed, the runlevels have direction settings 1 -> 2 -> 3 -> 5. Meaning, if you want your computer to boot to runlevel 3, runlevel 1 programs are started, then runlevel 2 programs then runlevel 3, and the system is booted. In this scenario, runlevel 5 programs are not started.

Then the init performs system initialization, named sysinit.

Depending on the runlevel, init tries to figure out if it is a part of a network. Then it mounts /proc, where Linux keeps track of various processes and hardware (try cat /proc/cpuinfo at the command line), and checks the BIOS to align the system with the BIOS settings such as date and time, and sets the time zone. After that init mounts the swap partition (which Windows users know as pagefile) as defined in the /etc/fstab. When finished, it goes on to setting the hostname, which is the system’s “name” in the network. After that, it mounts the root file system (/ in Linux notation) and checks the /etc/fstab again to verify the other file systems if specified.

Then it goes on to identify the Plug’n’Play devices in the system and makes the operating system aware of them by executing some routines. Init finally checks if there are any RAID devices in the system and verifies them. Reaching the last stages, it mounts all the file systems defined in /etc/fstab. Of course, if there are any other tasks specified in the /etc/fstab, init executes them also.

Logging in

When all of the above are completed successfully, init executes the /sbin/mingetty processes, which shows the graphical login screen of the distribution. Reaching this state means that the system is up and running in graphical user interface mode and waiting to know which user will log in.

Conclusion

This is an intricate step by step walk through of the Linux boot process. We have started from a basic “power off” state and reached the “graphical user interface” mode whereby a user can login. However, I must state that I am a little biased towards the distribution I am using, although I tried to be as distribution-neutral as possible. The location of the files/folders may differ slightly between Fedora/Debian/openSuSE/ArchLinux etc. but this does not mean that the system is working differently.

To understand how Linux works in enough detail to make boot or initialization tweaks, I suggest reading more about the boot process here in the Linux channel, and certainly to familiarize yourself with the wealth of material in the Learning Linux topic within the channel itself. This will help you when you want to execute administrative task, make changes to your system, or if anything goes wrong during the boot process and initialization of your Linux system.