What Caused the Tunguska Blast: An Asteroid, A Comet? 100 Years Later, Science Still Seeks Answers to Earth Impact in Siberia

A Blast in the Wilderness

One hundred years after something caused a massive aerial explosion in a remote and sparsely populated part of Siberia, the “Tunguska event,” as it’s known, continues to attract the attention of scientists around the globe.

The cataclysm took place on the morning of June 30, 1908, in a densely wooded region near the Tunguska River. For years afterward, the event was understood only through the accounts of eyewitnesses hundreds of miles away. They recalled seeing a large bright light moving across the sky, followed by a flash and a loud booming noise like artillery fire. The shock wave traveled hundreds of miles, too, shattering windows and knocking people to the ground.

It wasn’t until 19 years later that a scientific expedition actually explored the Tunguska area, finding millions of scorched and fallen trees, but no impact crater or remnants of the object that caused the damage.

A Devastated Forest

Photo credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Tunguska_event_fallen_trees.jpg

An Impact, But of What?

Today, most scientists agree a cosmic object of some sort – possibly an asteroid or comet – blasted through the Earth’s atmosphere at speeds of up to 33,500 miles per hour before exploding several miles above ground. The fireball’s superheated blast not only toppled 80 million trees over an area of 830 square miles, but obliterated the object itself. (Other theories, like those suggesting it was a tiny black hole, a chunk of antimatter or a crashing alien spaceship, still have followers but aren’t widely believed to be valid.)

That’s why questions still remain over what exactly the object was, as well as how big it was, how heavy it was and what it was made of. Was it an icy comet or a rocky asteroid? Was it a type of object with a minuscule chance of striking the Earth again in the next future, or are there many more objects like it out there that could impact again soon?

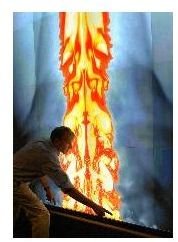

The Tunguska Fireball

Photo credit: Sandia National Laboratoies

New Insights

Late last year, for example, scientists at Sandia National Laboratories ran one of the most advanced supercomputer simulations yet on the Tunguska event. They concluded the object might actually have been much smaller than previously believed for the amount of damage caused. Upon exploding in midair, the simulation showed, the object set off a massive fireball that blasted downward toward the Earth’s surface faster than the speed of sound. That effect, coupled with new data taking into account topography and ecology (the forest was apparently not as healthy as once thought), indicated the impact might have been equal to a three- to five-megaton blast, rather than the 10- to 20-megaton explosion earlier models suggested.

Just two weeks after the Tunguska event’s 100th anniversary, an international team of scientists announced new findings to help dispel lingering theories the explosion was a purely terrestrial one (a naturally occurring nuclear reaction, for instance, or a “super-burp” of natural gas from deep underground). The team reported it had found high levels of carbon-13 and nitrogen-13 isotopes in the peat layer formed at the time of the impact, as well as evidence of a massive acid rain fallout: some 200,000 tons of nitrogen and nitrogen oxides.

“The levels of accumulation of the heavy carbon isotope 13C measured right on the 1908 permafrost boundary in several peat profiles from the disaster area cannot be explained by any terrestrial process,” said Tatjana Böttger of the Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research in Germany.

The team concluded the object hitting Tunguska could have been a C-type (carbonaceous) asteroid or a comet similar to Borrelly, which has been extensively studied by Deep Space 1 and the Hubble Space Telescope. (Observations have found that Borrelly is a dark, hot and dry comet, rather than a “dirty snowball,” with no detectable water ice at its surface.)

The Debate Continues

The mystery over what caused the Tunguska event lingers to this day in large part because researchers have never found any fragments of the impacting object, nor any signs of an impact crater, despite the widespread devastation the collision generated. Italian researchers Luca Gasperini, Enrico Bonatti and Giuseppe Longo helped renew debate in this area last year after publishing a paper suggesting that Lake Cheko, a 164-foot-deep lake five miles from the blast epicenter, could in fact be a low-velocity impact crater.

That assertion has raised plenty of objections – no fragments around the lake, no other secondary craters, apparently unaffected trees nearby – but Longo’s team is standing by the hypothesis and plans to continue studying the lake for clues. With the researchers set for a followup visit to the site this summer, we can perhaps look forward to one of the scientific journals soon publishing yet another chapter in the 100-plus-year-old Tunguska mystery.