A Brief History of Tuberculosis: The Discovery of the Cause of Tuberculosis

What is tuberculosis?

Tuberculosis is a disease that usually affects the respiratory system, but it can also affect the gastro-intestinal system, the central nervous system, lymphatic cells, bones, joints and even the skin. Its typical symptoms are a chronic cough with a blood-tinged sputum, weight loss and high fever. The impact of tuberculosis on the modern world is still incredibly significant, considering that one-third of the world’s population has been infected and that every second one more person becomes infected. In 2004 alone, 1.6 million people died from this disease.

Throughout the history of tuberculosis, when diagnostic techniques were not as advanced as today, the numbers of infected individuals must have been even more staggering, and the infection rate much higher. Even though this disease was so widespread and feared, no one before the 1800s had carried out any specific study of the causes and the characteristics of tuberculosis.

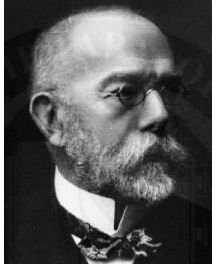

Robert Koch and the History of Tuberculosis

Robert Koch, sometimes considered the father of microbiology (though most often the title goes to Anton van Leeuwenhoek), was the first one to understand that the tuberculosis cause was microbiological in nature and he was the first to scientifically prove his conclusions. In fact, in 1882, Koch gave a lecture on the methodology he used to isolate and observe bacteria, and most significantly the bacterium that causes tuberculosis, leaving a whole audience of illustrious doctors and academicians speechless. Many of the people that were present at the lecture described it as one of the most, if not “the” most, important medical experience in which they had ever participated.

Beside his trusty microscope, which was indubitably one of the most important tools Koch used during his studies, success was also due to the techniques for the isolation and the identification of bacteria that he developed himself. Indeed, it was during Koch’s time that the germ theory of disease was beginning to gain importance and a number of scientists were eager to search for the microorganisms responsible for diseases; this led to the development of a number of methodologies for the isolation and identification of those microorganisms. Koch perfected many of those methodologies.

Creating a Medium

Observing a slice of potato that was mistakenly left exposed to the air, Koch noticed that several spots of different colors formed in different areas of the potato slice, and he understood that each of those colored spots must have been a colony of a certain type of bacteria. In this instance, Koch saw several types of different microorganisms separated from each other, while in traditional broth experiments they were all mixed together. This episode led him to the conclusion that he needed a proper medium in which different types of bacteria would be able to grow separately, allowing for a more attentive observation of individual bacterial types.

Koch created the medium he needed simply by adding gelatin to broth; unfortunately, when placed in an incubator, the heat would melt the gelatin, making the medium useless. However, with the help of one of his colleagues, Richard Julius Petri, Koch made a small, flat disk, with a cap and added agar, which is a Japanese compound that was used to make jam. The agar plate was born, revolutionizing the entire field of microbiology.

The Cause of Tuberculosis

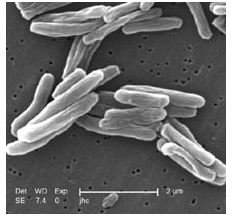

Because of his firm belief in the germ theory of disease, Koch hypothesized that tuberculosis was caused by a particular type of bacterium. With the new techniques and tools available for microbiological studies, Koch could start his research on tuberculosis, but he still needed something else to help him in his quest: a new staining method. Tuberculosis is caused by a rod-shaped bacillus bacterium, called Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which was not easily stained (and therefore not visible) using the methods common at the time when Koch first started his research. Luckily, Koch came across a new staining technique that had been newly developed by a physician, Paul Ehrlich; this stain was called methylene blue, and is still in use today even in undergraduate biology classes. Staining the bacteria with methylene blue allowed Koch to observe its singular shape and to verify its presence.

So with all his tools finally in place, Koch proceeded to test his hypothesis. He analyzed a huge quantity of tissue samples from infected animals and humans. He had collected these samples from material originating from the lungs and brain of people who had died from blood-borne disease, from the abdomens of cattle, and from the typical “cheesy masses” that are present in patients chronically infected with tuberculosis. In all cases Koch was able to isolate the bacteria that were present and to grow them in a pure culture. All the bacterial cultures created by Koch were the same, proving that the same microorganism was present in every observed case of tuberculosis and hence that that particular bacterium caused the disease. The discovery Koch made was of such significance and magnitude that it led him to win the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1905.