A Brief History of Book Publishing

Why Publish a Book?

Throughout history people published books for various reasons, ranging from archiving sacred knowledge (the scriptors in ancient Egypt for example were in league with the priests) to spreading ideas and ideologies (as in more modern times, for instance). Although the techniques of book publishing have changed a lot since the first books appeared, the motivations and the commitment of the writers has remained very much the same.

Publishing in Antiquity

The first books appeared in Mesopotamia sometime before the 6th century BC. The form of these books, as the ancient Sumerians, Babylonians, Assyrians, and Hittites wrote them, was that of tablets made from water-cleaned clay. These were related to cuneiform writing (the name of this script comes from the wedge-shaped marks made by the stylus in clay).

In the 6th century BCE the Aramaic language became more popular, and this type of publishing tech became obsolete, giving rise to the use of the papyrus.

The papyrus roll was widely used in ancient Egypt. Papyrus, which was made from the papyrus plant that can be found in the Nile Valley, was the predecessor of the modern book; in a way, more than the clay tablet.

In China, books were also produced on a large scale, though this came about after the Sumerians and the Egyptians. Although few surviving examples are before the Christian Era, there is a lot of evidence (both direct and indirect) suggesting that the Chinese had writing (and probably books) at least as early as 1300 BC. Those primitive books were made of wood or bamboo strips bound together with cords.

In Greece, books has a more practical character. The ancient Greeks adopted the papyrus roll and later on the Romans took it from them. Although both of these two civilizations used other writing materials too (waxed wooden tablets, for example), the Greek and Roman words for “book” identify with the model of the Egyptians. The oldest Greek rolls can be dated from the 4th century BC.

Rome was the channel through which the Greek book was introduced to the people of Western Europe. After the conquest of Greece by the Romans, the Romans took possession of the Greek libraries in order to build upon them similar ones in Rome. The latter had separate collections of Greek and Latin books. However, except for the change of the language, a Roman book closely resembled a Greek one in content, and imitated it extensively.

Moreover, the Romans developed a book trade on a fairly large-scale. From the 1st century BC there is evidence of large scriptoria turning out copies of books for sale. The well-known writer of that era, Cicero, even referred to bookshops while two centuries later, the poet Martial complained about professional copyists who became careless in their speed. The laws regarding trade, made by the emperor Diocletian, effectively set regulations for determining a price for books copying.

And Gutenberg Said: “Let There Be Printed Books!”

Ιn Medieval times, books were threatened like never before. During the 5th century when the Western Roman Empire broke apart with the roaming barbarians dominating the area, this threatened the existence of books. If it weren’t for the Church withstanding the assaults and remaining as a stable place to provide the security and interest in tradition, books would have been literally history. Books found asylum in monasteries where they were patiently copied one by one.

At the last part of the Medieval era, Johannes Gutenberg, an innovative inventor from Germany, came up with the printing press (1440-50). Though the focus at that time was the Bible – which remains the number one best seller of all time in the US – later on, other books were produced in Gutenberg’s press. To create the multicolored effect which is commonplace nowadays, the German inventor had to put each page into a press several times. Each one of them had to be aligned perfectly, and a different color ink was used for each impression. Gutenberg may have overdone things a bit, yet he couldn’t sell enough of his meticulously produced books to keep his creditors from shutting him down, and he died broke. Nevertheless, once Gutenberg’s process became known, scores of printers adopted the concept and printed books became widespread.

Renaissance and Industrial Age Publishing

From the mid part of the16th century through the 18th century, there were practically no technical changes in the methods of book production. However, book trading became something closer to what it is today. The bookseller now took onboard the key functions of publishing (selecting the material, bearing the financial risk of the production, etc.), something that previously was the domain of the printer. Afterwards, the shift continued towards the publisher and the author. The battle with the censor escalated before any measure of freedom of the press was permitted. Literacy grew steadily and the book trade expanded, both within and beyond the country borders.

Books in the 19th Century Onwards

After the 2nd World War, there were great changes in book publishing (or any other form of publishing for that matter). Electronic and communications technology revolutionized publishing, turning books into one more means of printed word, while magazines and newspapers started to dominate the scene. However, books were still very popular, though they were under two distinct banners: commerce and idealism. The copyright law was adapted and by the end of the 19th century, every country had some version of it.

In the 20th century, the effects of state education in the more developed countries became increasingly obvious. Standards of living progressed, and just like in earlier times, these two conditions brought increased use and publication of books. During the late 1890s and early 1900s, many new publishing houses came about. In the industrialized countries, though wages were rising, a small business could be staffed economically, and printing costs were such that it was economically feasible to print as few as 1000 copies of a new book. It was therefore comparatively easy to make a start, particularly because the long-term credit that printers were prepared to grant made a minimum of capital necessary.

All this has already started to shift though, as electronic publishing has opened the way to cheap book production, becoming more ecological and targeting a far more wide-spread audience. The number of e-reader devices has increased and now more and more authors prefer to have their work in electronic format too (if not exclusively in that format). It is becoming apparent that the future of book publishing may be quite different to what the history of book publishing has shaped. As more and more publishers realize that, the book is becoming literary a shapeshifter, a means of promoting knowledge and ideas, adaptive and flexible like its authors.

References

- publishing, history of. (2009). Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica 2009 Student and Home Edition. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica.

- http://www.cybercollege.com/frtv/book1.htm (last accessed: August 2011)

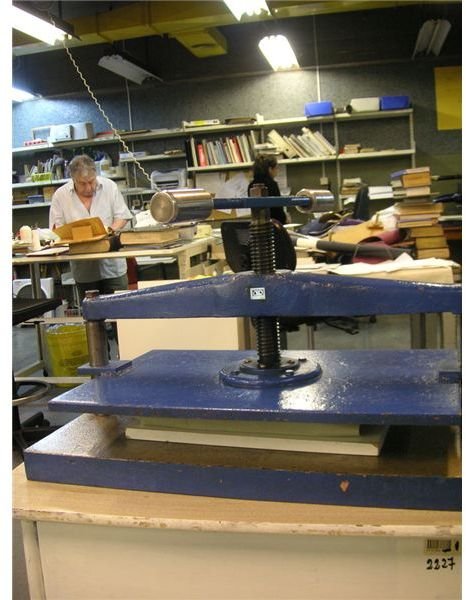

- photo originally by blmurch (www.flickr.com)