Japanese photographers, often overlooked, provide a unique view of the world.

Overview

The most riviting event in Japan’s history was the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by atomic bombs set off by the United States. The aftermath of these bombings at the end of World War II led to an photographic vison called “Are, Bure, Boke” according to the SF MOMA website, which means rough, blurred, and out of focus.

An example of a typical postwar image is Man and Woman #6, 1960, by Eikoh Hosoe, which contains a man with his head out of the frame holds the head of a woman, blurred and rough with abundant black shadows.

While Western photographers of 20th Century have become a sort of retro kind of entertainment at museums, Japanese photographers are often overlooked.

Considering the Japanese domonance of manufacturing photography equipment the influence of their photographers on the art of photography can’t be overlooked.

Terushichi Hirai

Beginning with the surrealist hand painted photographs of Terushichi Hirai, you can find a vast collection of imagery that parallels the development of Western photography. Hirai’s work rivals that of Man Ray, the photographer who led the rejection of modern art by creating bizarre surrealist images, such as the rotund woman’s back with insignias on either side. Hirai’s work included the surrealist Fantasies of the Moon (1938) photomontage, a creation a one-eyed head on a lower body donned in a pleated skirt with clunky high-heeled shoes under a partial moon.

Hirai was a founding member of the Tampei Photography Club, which promoted works similar to the Dada movement, which promoted surrealism and rebellion in art, in the United States and Europe. The era moved from Dadaism to Avant Garde, a time when Man Ray created Untitled (Study of legs), a surrealistic look at woman’s leg. Advertisers began to use ideas from these artists to promote products and services.

Both Japan and the Western world were looking for alternatives, some otherworldly, to the straight (realistic and sharp images) photography of Paul Strand and later, Walker Evans.

Masahisa Fukase

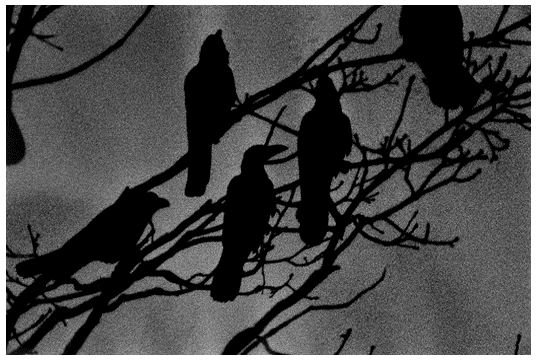

Known for his somber ravens and blackbirds, Masahisa Fukase created dismal symbols with the birds. Graeme Mitchell compares his work of the 1960s and 70s to French New Wave (La Nouvelle Vague**)** cinema, making fun of human foibles and creating bleak scenarios with an aire of distraughtness. American filmmakers such as Quentin Tarantino picked up the vib of this powerful imagery in the reckless characters that he created in his films.

Fukase’s book Karasu (Ravens) evokes the same feelings as the Alfred Hitchcock film, The Birds. The Guardian speculated that this book, published in 1986 is the best photography book of the past 25 years. The images break all the rules of current photographic standards of sharp images without noise. Fukase used noise (speckles of black and white dots) to create spooky settings.

The image above taken and developed by Masahisa Fukase has been provided by Robert Mann Gallery.

Eikoh Hosoe

In the 1960s Eikoh Hosoe composed images of people in extraodinary settings. His sense of distance to people is shown in a photograph of a man sitting on the edge of fence, far into the background of the frame and another of a woman circled in moonlight on a beach shot from considerable distance above her.

His close-ups of human torsos texturizes emotion. The gritty light shining on the contact of man and woman is one that is seemingly touched by the viewer, the emphasis being the value of that sense both between the opposite sex and the viewer’s erotic visualization brought on by the human contact.

As director of the Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts, Hosoe, hosts emerging artists’ work that celebrates the affirmation of life.

Daido Moriyama

As an assistant to Eikoh Hosoe, Daido Moriyama shot the underbelly of Japanese cities. Like other postwar Japanese photographers, he used noise that came from shooting with high ISO film as a mood-setter.

Alfie Goodrich writing for the Japonrama website called Moriyama, “the master of imperfection.” After shooting an underexposed image, he would overexpose the image when developing it, creating an illusion with dark shadows and blown highlights.

His subject matter ranged from bicycles piled on one-another to rabid-looking canines.

The Future

The current era, referred to as the Heisei era, a new generation of photographers who did not live through World War II, have a different viewpoint.

According to an interview with Marc Feustel, the curator of the 2009-10 exhibit, Japan: A Self Portrait, “Contemporary photographers tend to have a more detached, sometimes deliberately cold and distant approach and many more works deal with major societal issues through the prism of personal identity and the ordinariness of the everyday.”

One can look no further about the future of Japanese photographers by studying the work of the young artists at the popular 35 Minutes Gallery in Toyko.

The work of these artists range from close-up portraits to a study of the adult film industry.

The gallery is run by a group of artists who call themselves the 35 Minutesmen and who exhibit together once a month. It’s housed in an old photo processing plant, which has turned into a kind of performace space of people milling around an odd assortment of photographic displays.