What Are Hard Faults per Second (aka Page Fault), and How Many of Them Is Too Many?

Sluggish PC performance may have led you to start the Windows Resource Monitor from Task Manager or the Reliability and Performance Monitor from Administrative Tools in Control Panel. There, you observed a high utilization rate in both the CPU and the hard drive, and a section labeled “Memory” is showing dozens (or maybe) hundreds of hard faults per second. What are hard faults? Are they responsible for your PC’s slow performance? How many of them are too many, and what can you do about it?

_*Note: This article was recently updated to include a section for Windows 8 users.

_

Hard Fault vs. Page Fault

First of all, a “hard fault” was previously called a “page fault” in earlier versions of Windows. Perhaps page faults were more easily understood from the name, too. A hard fault happens when the address in memory of part of a program is no longer in main memory, but has been instead swapped out to the paging file, making the system go looking for it on the hard disk. When this happens a lot, it causes slowdowns and increased hard disk activity. When it happens an awful lot, the possibility of hard disk thrashing arises. That’s when a program stops responding, but the hard drive continues to run for an extended period. This has historically been referred to as “getting into the page file.”

In this era of relatively large memory, with most PCs having a gigabyte of main memory or more, hard drive thrashing and the problem of getting into the page or swapping file has become rare. However, it’s not impossible for a Vista computer with limited resources (too many programs running at a time) to be making a program read data continually to and from the hard disk. Each time this happens, it’s a hard fault. A high number per second suggests that something is running very slowly.

Memory Management in Vista

Let’s look more closely at how memory management in Vista works. When an application runs, it does not use all of its allocated memory at the same time. Some of the memory pages age. Some of them are modified before they are swapped. The memory manager keeps up with which were modified, which were just swapped because they are unused, and where they are in memory or in the swap file. The objective is to keep memory turning over in order to minimize (much slower) hard drive activity. Thus, using the swap file is just part of normal operations in Vista.

But what if performance really is lousy and the entire system is bogged down? Is it time to worry about too many hard faults? Maybe. A high number of hard faults, accompanied by high disk activity, suggests that one or more programs you’re running would benefit from having more RAM installed. You could also try moving your swap file (pagefile.sys) to another internal hard drive (not to another partition on the same hard drive). This may provide a benefit in that Windows can access the page file more quickly if it is not fighting a program trying to continuously read data from the same hard drive.

Also make sure that your page file is large enough. A size a little larger than installed RAM works very well. (Too small a page file can definitely cause a lot of page faults.)

Managing the Page File - Manual or Automatic?

In Vista or Windows 7, to check the page file size, press the Windows button on the keyboard or click the Start orb and type in “system.” In the search results at the top, click the item that simply says “System.” This is a shortcut to Start → Control Panel → System. Click “Advanced System Settings” and then click the “Advanced” tab. In the “Performance” area, click on “Settings.” In the resulting dialog, you should see your page file size under “Virtual memory.”

In Windows XP, right-click “My Computer” and select “Properties.” Then click “Advanced” and follow the same steps as in Vista.

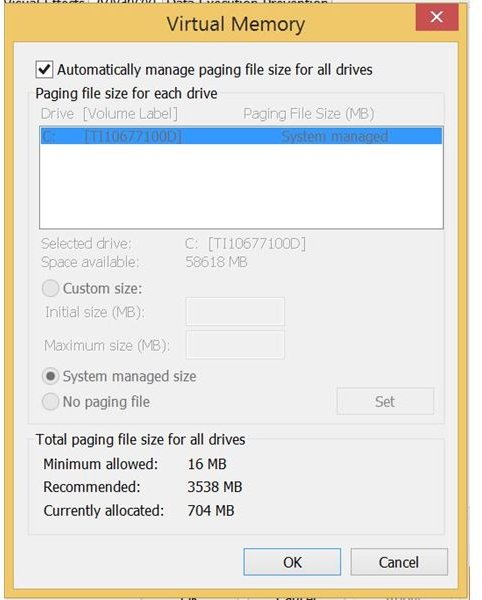

Should you let Windows “automatically manage the paging file size for all drives?” There are pros and cons involved. An advantage of Windows handling it is that you won’t run out of page file unless you run out of hard drive space. A disadvantage is that a variable file, unlike a fixed-size file, may become fragmented and cause even more hard drive activity. Of course, if Windows runs out of swap space in a fixed-sized file, it may promptly crash.

On my PC, I have three internal hard drives. One is a (faster) one TB drive, and another is a 500 GB drive that Windows runs from. I decided that I didn’t want a swap file on the C: drive at all, but I didn’t mind Windows handling the swap file automatically on the other drive. So I unselected “Automatically manage paging file size for all drives” and then clicked the C: drive. Then I clicked “No paging file” and “Set.” I did the same for the second hard drive. Finally, I clicked the one TB drive I planned to use, clicked “System managed file size” and “Set.”

For that drive, “Virtual Memory” is showing as Recommended: 4411 MB and Currently Allocated: 3241 MB. (The PC has 3 GB of RAM.)

If you prefer to manually manage your swap file size, try making it about 15% larger than your amount of RAM.

More on the Name Change

So adding more memory and moving or enlarging the swap file are positive steps that can be taken when there are too many hard faults per second. Seeing if there’s an update for the program causing the bottleneck may help, too.

But let’s look at the implication of Microsoft’s changing the name from “page fault” to “hard fault.”

There are actually three locations that items in memory can be in. One is in memory. One is on the hard drive in the swap file, and the third is in the “memory cache.” The cache is basically a small pool of the most recently used “pages.” These get to hang around in RAM for a while. If unused, they are moved out to disk. When a program requests the content of a certain item from memory, if it’s in main RAM, the program gets it very quickly. If it is in the cache, because it’s a memory-to-memory transfer, the program still gets it quickly. This is called a “soft page fault.” The thing to bear in mind is that this transfer is very fast- much faster than reading the content from the hard drive- so it can be considered a benign part of the operation of a paged memory system. However, if the needed page is no longer in the cache, Windows goes hunting it in the swap file, and this is a “hard fault” or “hard page fault.”

Microsoft doesn’t want us to worry our pretty little heads about the soft stuff, so they don’t tell us about it anymore.

Update for Windows 8

This update is provided by Ryan Tetzlaff.

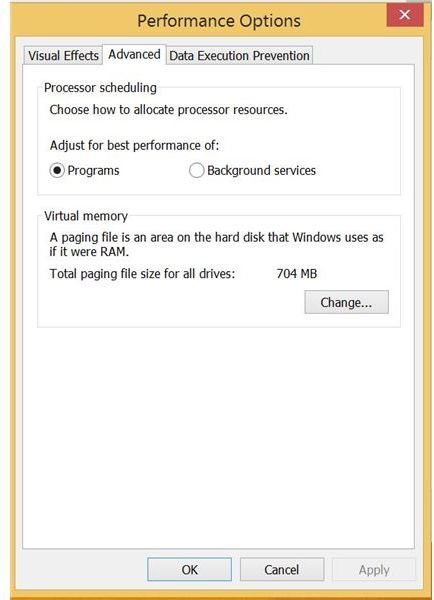

To find your Page file size in Windows 8, the instructions are similar to Windows 7. Open the Search Charms bar and type “System”. Start the “System” tool. From here click the Advanced System Settings link. On the System Properties window that opens, make sure you are on the Advanced tab. In the Performance area click Settings. In the Performance Options window click the Advanced tab and there you should see a section labeled Virtual memory.

As you can see in my screenshot I only have 704mb allocated to the paging file.

If you want to manually control your page file you can click the change button. Here Windows will make recommendations as to the size of your page file. Back when drives were mechanical there was a significant performance difference between using RAM and a hard drive. However, now that computers are more often being sold with solid state drives – SSDs, it is a good idea to let Windows manage the page file.

There is still a performance difference between memory and a SSD drive, but will generally not be noticeable to you. You can tell if you have a Solid State Drive by looking at the spec sheet for your computer or by examining your Device Manager. If you have a tablet or ultrabook you will likely have a SSD.

References

- Photo Credit: PhotoSpin