How Malware Works

Getting the Terms Right

Explaining how malware works requires a general understanding of the various types. Although covered in Part 1, the following is a quick review:

- Viruses - This type of malicious code cannot spread by itself. It relies on user or process interaction.

- Worms - Worms are designed to spread without any help from their creators, users, or processes.

- Keyloggers - Programs that capture keystrokes and send your passwords, PINs and other private information to others.

- Rootkits - This is actually a technology used to hide other types of malware from anti-virus applications.

There are other types of malware, but these are the most common–and the most disruptive–types crawling around the Web today.

How Viruses Work

Since a virus cannot spread by itself, a black hat (one of the “bad” hackers) has to attach it to something which he or she expects users to download and execute. For example, you might want to download a popular application available from one or more reputable sites. However, unknown to you, the copy you decide to download has something a little extra.

As shown in Figure 1, a virus is attached to the executable you stored on your PC.

When you run the application, the virus also runs, performing any of a plethora of unwanted activities, including:

- Attaching itself to other applications

- Deleting files

- Crashing your computer

- Stealing information

- Enlisting your computer in a botnet

- Using your contacts list to send itself, attached to some executable, to all your friends, family and colleagues

Viruses are not always attached to standalone programs. Sometimes malware works by combining with documents, such as a Microsoft Word file. Certain versions of Microsoft Word come with a programming language called VBA (Visual Basic for Applications). With VBA, a black hat can write virus code and attach it to an email attachment or send it via instant message. In most cases, all you have to do is open the file to set off the virus. Having a document appear in a view pane in Outlook is enough to kick it off.

Viruses, like most other malware, may or may not rely on known, unpatched operating system vulnerabilities. Again, getting the virus onto your computer requires assistance from people or processes. Worms do not have that restriction.

How Worms Work

Although worms perform many if not all the same tasks as an installed virus, they don’t rely on anyone or anything to propagate. Well, almost no one. As you will see in this section, negligence on someone’s part is very often the reason a worm finds its way around your network.

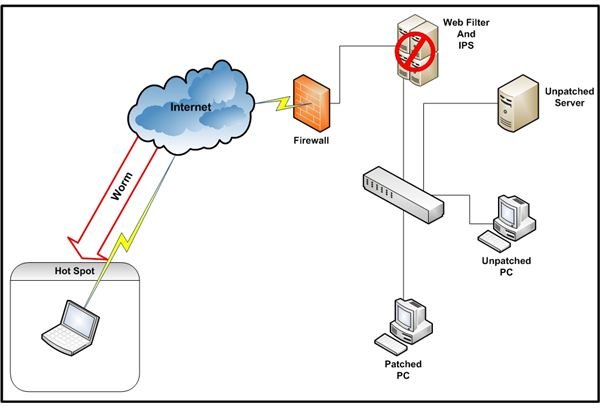

Figure 2 is a conceptual diagram of a business or home office network. The network is behind three standard perimeter defense components: a firewall, a Web filter and an intrusion prevention system (IPS). A detailed explanation of how these controls work is beyond the scope of this article. For more information, click on the links provided. Let’s assume, however, that a worm would have a hard time getting into this network from the Internet. Not impossible, just difficult. Then there is the laptop user.

In our example, a laptop user is attached to a coffee shop wireless hotspot. Although firewall, Web filtering, and IPS software are available for end-user devices, this organization does not use any of them. Further, the anti-virus software is not running the latest malware signature update. Therefore, when the worm waiting at a visited Web site saw the laptop, there was nothing to stop it from checking for the system vulnerability it was designed to exploit. Since the laptop was not patched for the vulnerability, the worm happily crawled across the network connection and made itself comfortable–without the user doing anything more than connecting to the site. It also started scanning any other computers the laptop detected in the coffee shop looking for other places to replicate.

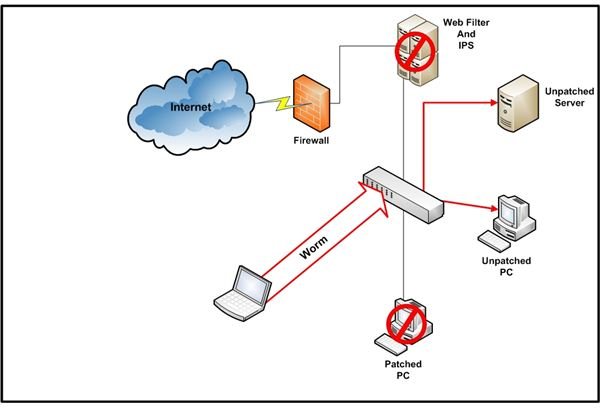

Figure 3 shows how malware works when the laptop user visited the corporate office. Since the laptop connected to the internal network, behind the perimeter controls, the worm had no difficulty in beginning a scan for vulnerable computers. In this example, a server and a PC were unpatched with out-of-date anti-virus software. The worm discovered these vulnerabilities in minutes and quickly spread to these unprotected computers. Note the protected PC was unaffected.

This is common way a worm finds a home in a network, but it is not the only way. Laptop users are not always the cause. Any user can go to the wrong place and pick up a worm even if using a desktop system. Once on a system, a worm begins its scanning.

Scanning by the worm, and all its replicas, can cause serious performance issues for network users. This is often the way an organization or individual discovers the infestation.

How Keyloggers Work

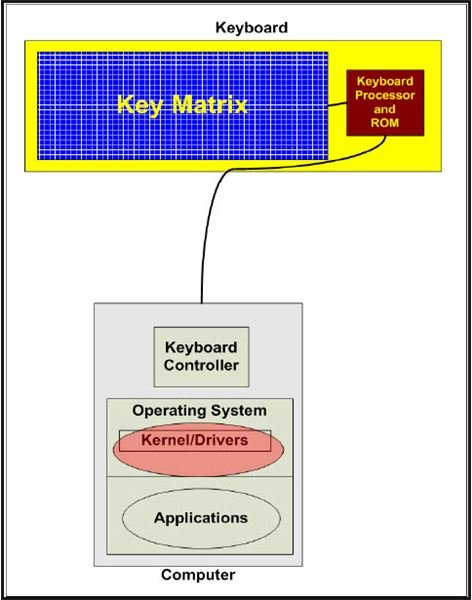

Keyloggers, or keystroke loggers, are usually deposited on a computer using a virus or worm. However, criminals who gain physical access to one or more computers also install them. Once installed, a keylogger positions itself as shown in Figure 4.

This common configuration allows capturing of the keystrokes sent from the keyboard controller, through the keyboard driver, to the operating system. The captured data is usually written to a text file for manual retrieval or automatic upload.

Keyloggers are difficult to see since they are usually installed using rootkit technology, defined in the next section.

How Rootkits Work

Rootkits creep into networks via multiple paths, including email, instant messaging and spyware. When they reach a computer, they bury themselves so the operating system, and therefore anti-virus applications, can’t see them. No matter where you look, including the list of running processes, the hidden applications will not appear. Once hidden, these applications, often taking the place of actual operating system modules, run in response to system calls, including drivers and kernel functions.

There are two basic types of rootkits: user mode and kernel mode. Using API functions, user mode rootkits modify the paths to executables. The advantage of this approach is ease of development. The disadvantage for a black hat is that user mode malware is easier to detect.

Although more difficult to develop, kernel mode rootkits are easier to hide. Instead of leveraging APIs, they exploit undocumented or unpatched OS structures or vulnerabilities.

Whichever approach an attacker chooses, rootkit technology can install and hide some of the most destructive or disruptive malware. Once on a computer, the only way to be sure it is completely gone and will not reinstall itself is to format the hard drive and start over.

In Part 3 of this series, we begin looking at other ways to effectively deal with malware.

This post is part of the series: Understanding Malware

This series of four articles describes the types of malware, how they negatively affect our lives, and how to combat them.