About Prion Disease in Humans: Symptoms and the Genetics Behind it

What Are Prions?

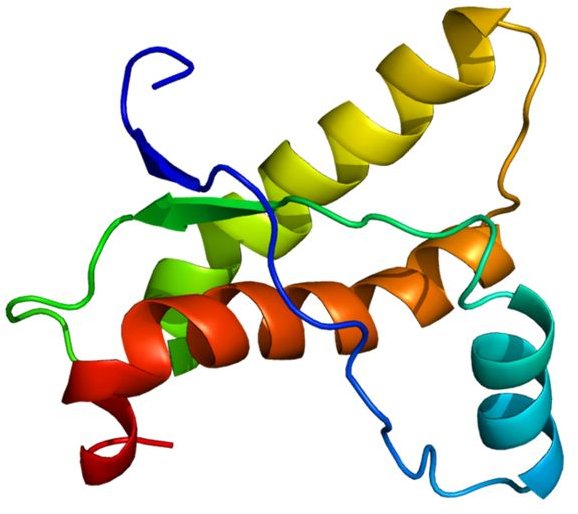

Prions are a malformed version of a protein found in cell membranes. Prions can turn the normal version of the protein (called PrP) into the malformed version - meaning, basically, that once one is in the body, all the normal versions can become prions too, and they spread at an exponential rate. They are also fairly indestructible. They resist the body’s normal cleanup enzymes (called proteases) which remove proteins that are no longer needed, and they are not destroyed by standard medical sterilization techniques like autoclaves.

Prion Disease Symptoms

Prions build up as a fibrous material that makes plaques and causes cell death. When this happens in the central nervous system, it disrupts normal brain functions, causing symptoms like personality and behavior changes, psychiatric issues, speech problems, memory problems, ataxia (problems with muscle coordination), hallucinations, dementia, myoclonus (sudden jerky motions), insomnia (permanent in the case of fatal familial insomnia), convulsions, coma, and eventually death.

Which symptoms appear depends on which parts of the brain are affected, and the only way to confirm a diagnosis is by looking at the brain after death. The brain takes on the appearance of a sponge, with many small holes where nerve cells have died.

Medical Terminology

Prion diseases are also called transmissible spongiform encephalopathy - transmissible because they can infect others (though not in the usual ways of infectious diseases), spongiform for the sponge resemblance, and encephalopathy which is the general term for brain disease. Prion diseases currently cannot be treated and have no cure nor vaccine, though medical research continues to search for them.

Human Prion Diseases

There are three types of prion diseases in humans - Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and kuru, Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker syndrome, and fatal familial insomnia. There are also three types of origins - inherited, acquired (infected), and sporadic (exact source unknown). All are rare, though Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease is more common than the others and probably the most well-known for its relation to the version found in cows, bovine spongiform encephalopathy, also known as “mad cow disease.”

Inherited Prion Diseases

Most cases of Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker syndrome (GSS) and fatal familial insomnia are inherited, as are 15% of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease cases. All are autosomal dominant, which means there is a 50% chance of having the disease if either parent has it (or 67-75% if both do).

Acquired Prion Diseases

In about 85% of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease cases, the prion is acquired from outside the body. Most are due to contact with central nervous system tissue of a person or animal with the disease. Contact might be direct, as in handling or eating their body tissues, using growth hormone made from human pituitary glands rather than synthetically, or blood transfusions from an infected source. Kuru was passed around in Papua New Guinea because the culture of the Fore Tribe included eating their deceased family members, including the brains. The variant related to “mad cow disease” comes from eating infected beef.

Or it might be less direct such as through surgical implements that were previously used on a patient with the disease. Nowadays such implements are destroyed after use on someone who has or is suspected to have a prion disease.

Sporadic Prion Diseases

No one is quite sure what causes the sporadic versions of GSS, fatal insomnia, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. It’s possible that one protein molecule of PrP is spontaneously malformed in just the wrong way, becomes a prion, and then goes on to infect all the others.

Prion Genetics

All prion diseases come from mutations of the same gene (called PRNP, the one that codes for the normal version of the protein found in cell membranes), which is located on chromosome 20 in humans. There are about fifty different known alleles of the human gene. Most of these don’t result in prions, though they may predispose their carriers toward developing prion diseases if infected. One is known to provide resistance to kuru.

No one is quite sure what the normal version of the protein does in the body, though research continues on that front as well. Since it’s found in every cell in the body, it’s probably fairly important. It might be involved in transferring copper into cells. In the brain, it seems to have a role in forming memories.

References

Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Foundation, Inc.

S. Collins, C. A. McLea, and C. L. Masters. 2001. Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker syndrome, fatal familial insomnia, and kuru: a review of these less common human transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 8(5): 387-397.

Photo Credits

Prion protein picture by Emw (CC-A-SA 3.0).