Colophon Examples: Learn What They Are and See Some Samples

Printing Terminology

Since the inception of mass printing, there have been various terms used to describe different aspects of the process. Some of these terms are used so often that as the industry grows they can end up taking on multiple meanings. This is exactly what has happened to the term colophon in the printing world.

Today, this term is used for two meanings. The first meaning is for publishing notes, while the second meaning alludes to a printer’s logotype or watermark. Here we will explain each meaning and give colophon examples to show you what each should look like.

Start of Printing Use

There is no specific date denoting when the colophon began to be used, but we do have some history on its use in printing. Some older use has been alluded to for inscribed tablets and papyrus writings of ancient Egypt dating to the collection of the first Alexandrian library. Using colophons enabled historians of the time to keep track of who wrote what and where the text came from. Although the library caught on fire in 48 BC, through the process of saving some items and moving them, the practice of colophon continued to grow.

It is interesting to note that the study of colophon use has been documented by Richard Minksy as preceding text publishing. Through the Center for Book Arts, some of his founding research has included the illuminated genre as also containing the use of colophon before plain text printing became standard.

The word itself comes from the Greek base of κολοφων carried over to the Late Latin of colophon. In Greek, the word translates to “finishing,” which is what the item does to a publication: it rounds the piece out with additional information.

Publishing Notations

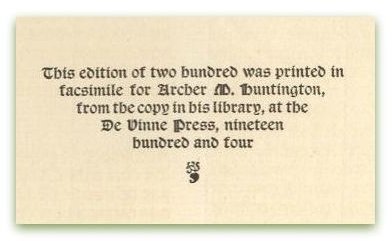

The first colophon meaning - that of publishing notes - has become the most common definition of the term. Under this meaning, the colophon is an accumulation of the printer’s names, date of publication and printer’s address placed in the back of the book. Sometimes additional information was included such as the editor’s name or the proofreader’s name.

Generally placed at the end of the publication (depending on the printer), the colophon could be switched and placed on the opposite side of the title leaf page at the start of the book. An example of what this form looks like when printed can be seen in the image at the upper left.

Printing Marks

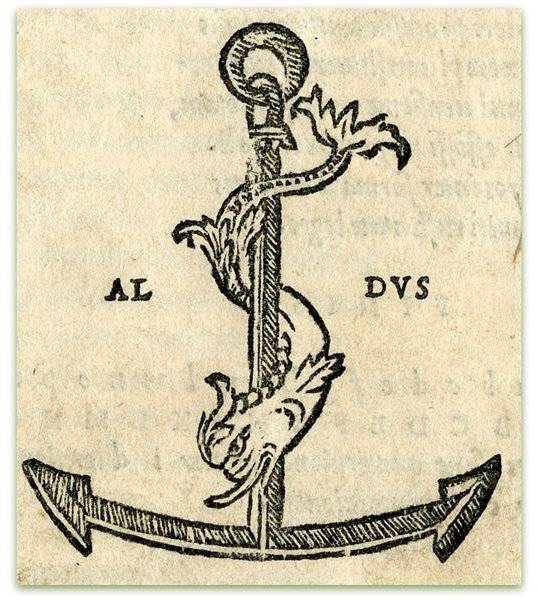

As the flourish of the Renaissance movement grew, publication information became less text based and more artistic. Printers began to stamp or imprint their own logo with the date of publication, the printer’s address, and the names of the head of the printing firm. This artistic way of adding the colophon information became so widely used that it branched off into a realm all its own called printer’s marks.

One of the earliest examples of colophon information in a printer’s marker is that of Aldus Manutius. Aldus was an Italian printer who founded the early publishing house of Aldine Press of Venice in 1494. Shown in the image at the left is one of Aldus Manutius’ marks. Because of the artistic quality of his mark, the style became used through many publishing houses throughout early modern Europe.

Modern Day Usage

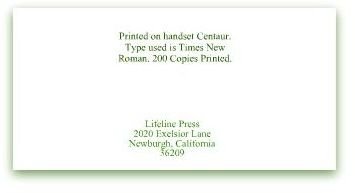

Colophons used today are not quite as flourished as the earlier example. Even their location is moved around in publications, and this is only dependent on a publisher’s preferences. Many of today’s mass printed books have the colophon located in the front before the table of contents, but there are some small publishers that still use it in the back of the book.

In the image at the left is an example of what many see in today’s publications. Simple text, clean font, and basic information are normally the standard of most modern publishers. Although some publishing houses are well known enough by their mark alone, there remains a few that still use a printer’s mark exclusively as the colophon.

References

The Richard Minsky Archive, https://www.library.yale.edu/arts

Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe, Cambridge University Press, 2005

Paul J. Angerhofer, Mary Ann Addy Maxwell, Robert L. Maxwell, Pamela Barrios, In Aedibus Aldi: The Legacy of Aldus Manutius and His Press, Friends of the Harold B. Lee Library, 1995

Image Credit: 1st colophon example, The Elizabet Nesbitt Room of the Information Sciences Library at the University of Pittsburgh

2nd colophon example, University of Massachusetts Amherst Library

3rd colophon example, author created, all information used in image is fictional