Paris and the Documentary Photography of Eugene Atget

Atget as Actor and Painter

Eugène Atget was born in 1857 in Libourne, France, the son of a carriage-maker. Both his parents died while he was young, so he was raised by his grandparents and sent to sea as a ship’s boy in the merchant navy. As an adult, he lived in Paris, a city he loved for the rest of his life. He began his artistic life not as a photographer, but as an actor. He studied acting at the Conservatoire Nationale de Musique et de Déclamation in Paris, but did not graduate. For a time, Atget worked as an actor in a troupe of traveling players, where he met his lifelong lover and companion Valentine Delafosse Compagnon. She later became the only assistant he ever had in his photography studio.

When he gave up acting due to problems with his throat, Atget next turned to painting for a couple of years. His was unsuccessful as a painter, but while he was trying it out, he had also taken his first photographs, and it is photography that became his life’s work.

Documents for Artists

I

n 1890, Atget set himself up as a photographer of “documents” for artists. He began to shoot buildings and other things that would be useful for painters, sculptors, architects and others, and sold prints inexpensively to be used as reference images. Throughout the 1890s, images of buildings and other particularly urban subjects became more and more a part of his work and resulted in the acquisition of a new kind of client: museums and public institutions.

At least since the urban renewal of Paris by Baron Haussmann in the 1860s, there had been interest in recording the national heritage of France, particularly the architecture. So much of the medieval city had been lost in Haussmann’s efforts to turn Paris into a modern metropolis, that there was a renewed interest in preserving, or at least recording, what was left. What this meant for Atget was that there were a number of museums and libraries interested in buying prints from him. In 1920 he was even able to sell a significant portion of his archive of negatives, bringing financial security for years afterwards.

Paris in Series

Atget began shooting a variety of subjects to meet the reference needs of his artist clients, but with the interest in his photographs as records of the history of Paris, his focus shifted to Old Paris in particular. He began to thoroughly photograph the part of the city that had been left intact during the urban renewal of the 1860s.

Atget was not the only photographer to work on documenting the city–various public programs to record old buildings had been instituted–but he is the one most remembered now. Atget didn’t work for any of the government programs, but instead took his photographs and sold them to public institutions afterwards. This meant he had much more freedom to shoot his pictures however he liked and, though he tended to use a fairly straightforward style, it let him develop his own particular way of looking at his subjects.

Posthumous Influence

Though he was not an art photographer–and in fact, his work was a considerable departure from the attempts of 19th century photographers to make “painterly” images– Eugène Atget had considerable influence on photographers who followed him. The Surrealists attempted to adopt Atget as one of their own. Man Ray, for example, had a collection of Atget prints and even published some of them in the journal La révolution surréaliste. Atget however, asked that the work be published anonymously, because they were “nothing but documents.”

Man Ray’s assistant at the time, soon to become known as a photographer in her own right, was Berenice Abbott. She began to collect Atget’s work as well, and visited the elderly photographer in his studio beginning in 1925. When Atget died in 1927, not long after Abbott took his portrait in her own studio, she enlisted the help of filmmaker Julien Levy to buy Atget’s remaining archive of approximately 1300 negatives and 5000 prints. She worked tirelessly to bring Atget’s work to the artistic community, putting on an exhibition and publishing a book of his photographs. Her efforts made Eugène Atget’s work popular until around 1930 when interest waned.

Abbott did not give up, however, and in 1968 she donated her collection of Atget’s work to the Museum of Modern Art (affectionately known as the MoMA) in New York City. This sparked another wave of interest in Atget, and he has remained an important figure in the history of photography ever since.

Precursor to Art Photography

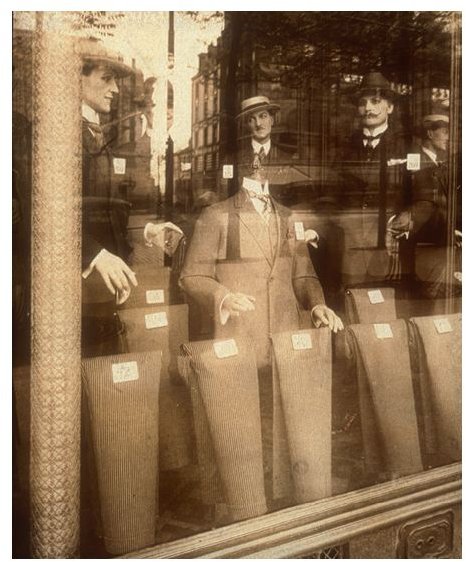

Although critic and philosopher Walter Benjamin heralded Atget as a precursor of Surrealist photography (where his influence is definitely apparent, especially if you consider the images containing interesting juxtapositions caused by reflections in shop windows), he was even more important as an influence on documentary photography and a precursor of the Modernist movement.

Documentary photographers like Bernd and Hilla Becher were certainly affected by the way Atget’s seemingly simple images could hold more meaning than the sum of their subject matter would indicate, and they took the approach of photographing structures in a simple, straightforward manner even farther in their own work. Thus, Atget became a hero of the “straight photography” movement, too.

There is some debate about whether or not the elements that make Atget’s work “art” today were intentional or simply accidental results of the way he shot. There is doubt, for example, that the juxtapositions created by reflections and the psychological affects of slightly off-centre framing seen in many of his images were deliberate. Berenice Abbott, however, pointed out that Atget was working with a view camera and very large glass-plate negatives (the standard size was 18 by 24 centimeters, or not quite 8 by 10 inches). It’s simply not possible, she said, to frame and focus an image on a ground glass viewfinder of that size without noticing pretty much everything in the image.

Interestingly, though smaller cameras were coming into wider use at the time, and Man Ray even offered Atget the use of a Rolleiflex, Atget refused to use any other equipment. Small cameras, he said, worked faster than he could think. And besides, it was partly the limitations of his equipment that allowed Atget to create images that are uniquely his.

References

- The Photography Book. Phaidon Press, 2000.

- Image 2 Credit: Une vitrine Avenue des Gobelins à Paris by Eugene Atget, 1927. Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.

- 20th Century Photography: Museum Ludwig Cologne. Taschen, 2001.

- Newhall, Beaumont. The History of Photography. Museum of Modern Art, 1982.

- Krase, Andreas. “Archive of Visions–Inventory of Things: Eugène Atget’s Paris.” Paris: Eugène Atget 1857-1927. Taschen, 2000.

- Abbott, Berenice. “The World of Atget.” Photography in Print: Writings from 1816 to the Present. Edited by Vicki Goldberg. Touchstone, 1981.

- Image 1 Credit: Organ Grinder by Eugene Atget, ca 1989. Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.