How does the Rhino Survive in its Habitat: Survival Mechanisms

Rhinoceros Species

Rhinos existed back in prehistoric times and once flourished in large numbers, living in diverse habitats across Africa, Asia, Europe and North America. Today, due to poaching and habitat loss, very few remain. Since 1970 alone, the rhinoceros population has declined by approximately 90 percent, according to the American Wildlife Foundation. As of 2010, there are five species of rhinos totaling approximately 24,500 in the wild and 1,250 in captivity, reports the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The White Rhino is under threat of extinction and the other four species are on the verge of extinction. The five remaining species are:

White Rhino (Certotherium simum)

Number in the wild: 17,500

Location: Africa’s savannahs

Black Rhino (Diceros bicornis)

Number in the wild: 4,240

Location: Africa’s grasslands, savannahs and tropical bush lands

Greater One-Horned Rhino (Rhinoceros unicornis)

Number in the wild: 2,800

Location: Northern India’s and Southern Nepal’s flood plains, grasslands and woodlands

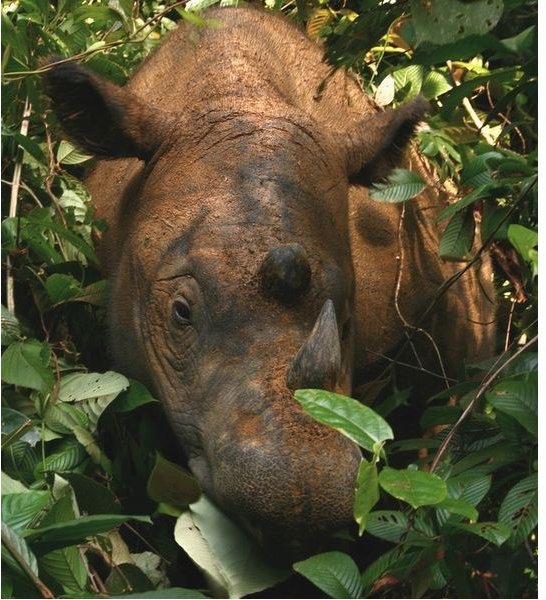

Sumatran Rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis)

Number in the wild: 200

Location: Dense tropical forests of the Indonesian island Sumatra and on Borneo

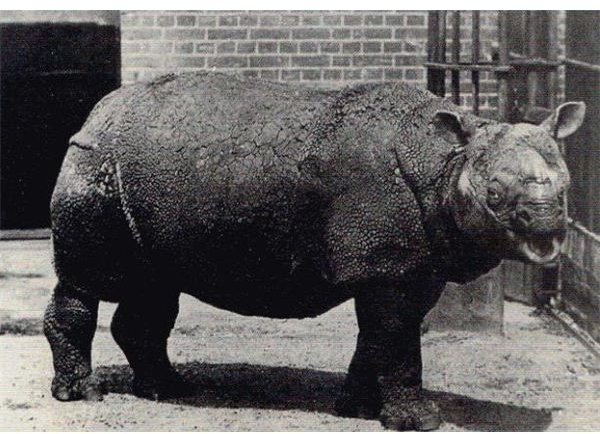

Javan Rhino (Rhinoceros sondaicus)

Number in the wild: 40 to 50

Location: The majority of the remaining Javan Rhinos (35 to 50) live in Ujung Kulon National Park, located in Indonesia. A few (less than five) live in Vietnam’s Cat Tien National Park. No Javan Rhinos exist in captivity.

How the Rhino Survives

Rhinos are herbivores and approximately 27 to 37 pounds of vegetation a day. To meet the demands of their diet, they live in densely vegetated grasslands, savannahs and tropical forests of Africa, Northern India, Southern Nepal, Indonesia and Vietnam. They spend about 50 percent of the day, traveling a few miles daily, eating a wide-variety of grasses to meet their dietary needs. The Black Rhino however, has a prehensile lip that it uses to grasp leaves and twigs to feed from trees and shrubs, instead of grasses. To deal with hot weather, rhinos tend to rest during the heat of the day and forage for food in the mornings and evenings. Rhinos need to drink large amounts of water to hydrate themselves and cool off their bodies, so a rhino’s territory must contain water. Each rhino has a territory range of about 12 square kilometers. They prefer to drink daily, but can go several days without water when necessary. During dry seasons, they often travel farther than normal to find water, extending their territories to 20 square kilometers.

Survival Mechanisms

Rhinoceroses have many features and techniques they use to survive in the wild. These survival mechanisms include:

Size

Rhinoceroses are huge. They are the second largest land mammals in the world; elephants are the largest. The White Rhino is the biggest of the five species, weighing up to 6,000 pounds and the Sumatran Rhino is the smallest, weighing up to 2,000 pounds. Being such a large size, adult rhinos do not have much to fear in the animal kingdom. In fact, humans are their only real predators. Calves (baby rhinos) that are still small enough to attract predators are protected by their mothers who stick close by, scaring off any animal who intends them harm.

Speed

In addition to their large size, rhinoceroses are really fast. Rhinos have big feet that are capable of supporting their large bodies, while enabling them to run really fast. Depending on the species, rhinos can run up to 40 mph. Imagine a rhino running as fast as a car towards you! When a rhino feels it is in danger, it charges full-speed at the object of its fear. Usually, this is just an act of intimidation to try to scare a predator away, but if necessary, the rhino will run into and ram a predator that fails to seek cover. The rhino is also quite agile, despite its large size and can quickly maneuver and turn in tight areas.

Horn

Rhinoceroses have one or two horns – depending on the species – located on the front of the face, above the nostrils. The horns are made out of narrow, tightly matted together tubes of keratin (the same substance human hair and nails are composed of). Rhinos use their horns to defend themselves against predators and during mating fights. Sometimes during mating time, two males will fight with each other over a female. Very occasionally, two females will fight over a male. A piercing jab from the horn can be deadly. Sometimes during a fight, a horn will fall off, but grows back slowly over time.

Skin

Rhinos have thick skin that is difficult to penetrate, protecting them from predators and thick brush in the habitat. The skin looks rough and leathery, but it is actually quite soft and sensitive. Rhinos frequently roll in mud wallows, coating themselves with mud, which protect their skin from sunburn, insects and to keep cool in hot weather.

Senses

Rhinoceroses have poor vision. Their vision is so poor that they have been known to barge into trees, mistaking them for predators. To make up for their poor vision, they have an excellent sense of smell and hearing. They can rotate their ears to enable them to locate sounds coming from different directions and they use their sense of smell to detect predators and to communicate with each other. By smelling the urine and dung from other rhinos, they can detect the boundaries of other’s territories and when others are ready to mate.

Symbiotic Relationship

The tick bird – called askari wa kifaru in Swahili, which means the rhino’s guard – and the rhino have a symbiotic relationship. The bird eats ticks and other insects off the rhino’s skin and raises a noisy fuss when something is near, alerting the rhino to danger.

Conservation

The future survival of rhinoceroses is a major concern. Wildlife officials are constantly battling to stop poachers and prevent habitat loss.

Although killing rhinos and selling horns is illegal, the market is still strong. There is a strong demand for the horns primarily in China, Taiwan and South Korea. They are used in traditional Asian medicines as a treatment for ailments, such as headaches, impotence, fever and devil possession, despite the lack of scientific evidence that the horn is an effective remedy for any ailment. More recently, rhino horns have been falsely touted as a cancer cure – with no scientific evidence – which has increased poaching activity.

The pharmaceutical company, Hoffman LaRoche and Dr. Raj Amin of the Zoological Society of London ran extensive tests on rhino horns. The test results showed conclusively that rhino horns had absolutely no medicinal qualities. Despite these test results, approximately 60 percent of traditional Asian medical practitioners stock rhino horns for their practice, according to survey by TRAFFIC.org. The horns sell for $57,000 a kilogram on the black market, which is quite an attractive price to poachers. The high selling price of the horns has brought about a sophisticated breed of poachers. Dr. Joseph Okori, the WWF African Rhino Program Manager said, “This is not typical poaching.” These sophisticated poachers utilize helicopters, night-vision equipment, tranquilizers and gun silencers to kill rhinos in reserves without attracting attention from wildlife law enforcement patrols.

Another cause of the decline of rhinos are human activities such as road projects, dam construction, agriculture and the construction of buildings, which continually encroach into the rhinoceros’s habitat.

Conservation efforts have made some progress over the years with conservation efforts. Numbers of White Rhinos, Greater One-Horned Rhinos and Black Rhinos have increased, although, there are still far too few remaining to cease conservation efforts. Recently, however, illegal poaching is again on the rise. In the first half of 2011, almost 200 rhinos were killed in South Africa alone. In 2010, in Vietnam’s Cat Tien National Park, a female Javan Rhino (possibly the last in the area) was found dead with her horn chopped off. On a more positive note, the World Wildlife Fund released videos in 2011 that showed two female Javan Rhinos with their calves in Indonesia’s Ujung Kulon National Park.

Several methods are being undertaken to conserve the rhinos including stopping human encroachment on habitats, establishing and expanding protected habitats, relocating rhinos to safe habitats, patrolling reserves and habitats to catch poachers, improving laws to fight poaching, enforcing stiffer penalties for poachers and promoting tourism that will increase funding for conservation. Money is always an issue. It is expensive to monitor habitats for poachers. Fortunately, wildlife funds are helping fund conservation efforts.

Rhino Images

References

Rhinos; IUCN; May 2, 2010; www.iucn.org/es/aib/acerca_de_la_biodiversidad/biocuriosidades/?5152/rhinos

Rhinoceros; AWF; www.awf.org/content/wildlife/detail/rhinoceros

Rhino Poaching Surge Continues in 2011; July 4, 2011; www.traffic.org/home/2011/7/4/rhino-poaching-surge-continues-in-2011.html

Dramatic Video Footage Confirms That Javan Rhinos are Breeding; Rhinoconservation.org; February 27, 2011; www.rhinoconservation.org/2011/02/27/just-released-exciting-new-videos-of-javan-rhinos-and-calves-in-indonesia/

Rhino Fact Sheet; International Rhino Foundation; www.rhinos-irf.org/attachments/wysiwyg/4/RhinoFactSheetFINAL.pdf

Rhinoceros; WWF; wwf.panda.org/what_we_do/endangered_species/rhinoceros/

Rare Javan Rhino Found Dead in Vietnam; WWF; May 10, 2010; wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?uNewsID=193168

25 Things You Might Not Know About Rhinos; International Rhino Foundation; www.rhinos-irf.org/25-things/

Image Credits

White Rhino Image Credit: Chris Eason/ creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en

Black Rhino Image Credit: Matthew Field/ creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/deed.en

Greater One-Horned Rhino Image Credit: Hans Stieglitz/creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

Sumatran Rhino Image Credit: Bruce1ee/Public Domain

Javan Rhino Image Credit: The Zoological Society of London/Public Domain