What is Progeria? A Look at the Genetics of Progeria Disease

Progeria Disease

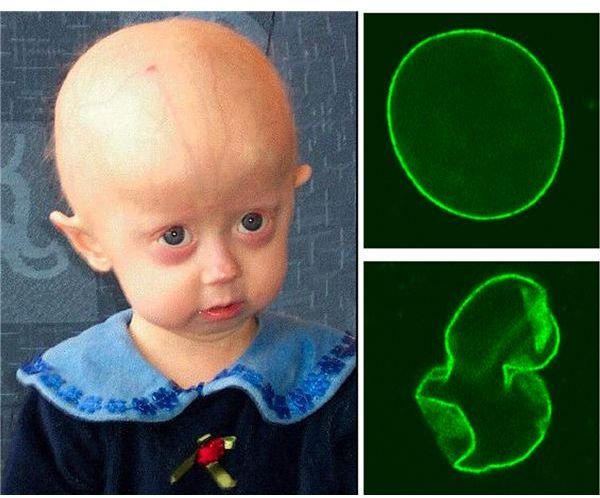

Progeria disease is actually called Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS). People with the accelerated aging disorder may experience dwarfism, baldness, osteoporosis, wrinkles, hardened arteries, and late developing or no teeth. The average life expectancy of someone with the condition is between 13 and 16 years, though some people have lived to their late teens and others to their twenties. Progeria affects boys and girls in equal measure, and all races.

The condition was discovered in 1886 by Jonathan Hutchinson who described a six year old boy with no hair and atrophy of the skin.

The Genetics of Progeria

Progeria is not an inherited condition; typically it occurs as a random mutation, although there is a heritable form. The fault lies with a point mutation on the LMNA gene at position 1824 - a cytosine base is replaced by a thymine base. This creates an unstable form of the protein the gene codes for which is Lamin A, and this results in a misshapen cell nucleus. The Lamin A protein is part of the scaffolding that holds the nucleus together. But when the nucleus is misshapen it somehow leads to the symptoms of the disorder, though the mechanisms by which this occurs is largely unknown.

Searching for a Progeria Cure

Death usually occurs as a result of heart disease, and therefore any cure or treatment could benefit millions of people around the world as heart disease is one of the biggest killers.

-

At the time of writing (September 2009) there is a phase II clinical trial of farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs). Previously these drugs had been shown to correct the abnormal shape of nuclei in lab cell cultures. In addition Progeria mice treated with FTIs overcame their symptoms. The human trial is due to report its findings in 2010.

-

A triple drug trial will use current FTI treatment as well as two other drugs called pravastatin and zoledronate. This follows on from lab studies by Dr Carlos Lopez-Otin of Spain which showed that these two drugs not only improved the disease in cell cultures, but also extended the lifespans of Progeria mice.

-

Gene therapy may also be a potential future treatment, though it is too early to know if and when. In 2005 scientists from the National Cancer Institute were able to correct the genetic mutation in the Progeria gene by applying morpholino oligonucleotides - “molecular sellotape.” The oligonucleotides repaired the mutation so that the gene was functioning normally.

Genetic Testing

A genetic test for Progeria is available. Children with the condition appear normal at birth as symptoms materialise within 12-24 months. Previously diagnosis could only be made when the physical symptoms appeared, but a genetic test means a child can now be diagnosed sooner, and treatment initiated earlier in the disease process. The test can also help to reassure parents that the condition is a result of a random mutation, and that it will be unlikely that future offspring will have the genetic disorder.