Uses of Rockets--From War Weapons to the Sound Barrier

A Weapon of War

Rockets were used in warfare by the Chinese, who invented black powder, more than 2000 years ago. They were the first artillery pieces. Even after the invention of the canon, rockets continued to be used as artillery. In the Revolutionary War, the British attacked forts from the sea with rockets. In the War Between the States, rockets were used primarily as means of signaling, but some artillery rockets—very primitive ones—were used by both Union and Confederate troops.

It was not until WWII that rockets began to be used extensively in warfare. At first, they were used as air launched powered bombs to attack ground targets. Towards the end of the war, they became more powerful, and development began on air-to-air rockets for aerial combat.

Of course, the major advance in rocket use in WWII was Germany’s development of the V2, the world’s first ballistic missile.

But the V2 was not Germany’s only use of rockets. It also flew the world’s first rocket powered aircraft—the ME-163. This stubby fighter caused dismay within our bomber fleets. It would dive through them at nearly 500 mph, firing its canon continuously, and be gone before the crews could react.

Fortunately, the rocket plane used most of its fuel on takeoff, and could make just one pass through a bomber formation before heading back to base for a gliding landing on a skid. But the concept would be resurrected for research craft when the U.S. began assaulting the sound barrier.

Sounding Rockets

After WWII, the V2 was used in the U.S. for upper atmospheric research, as a sounding rocket. It gave rise to a home grown sounding rocket, the Viking. At the same time, another, smaller sounding rocket was developed, the Aerobee.

Sounding rockets were used to determine the makeup of the upper atmosphere. At the time, we had no real idea of what the atmosphere above 50,000 feet was like, or even how far it extended above the surface of the planet.

The sounding rockets also carried instruments that gave us brief glimpses of the Sun. This began giving us our first clues as some of the secrets of our star.

Since those early years, new sounding rockets have been developed. There is still much we need to learn about our envelope of air, and universities around the globe are using these new rockets to sample various layers of our blanket of life.

Testing the Sound Barrier

As jet aircraft flew faster and faster, they began experiencing strange phenomena. Especially in dives, the controls would reverse. Pulling back on the stick wouldn’t cause the plane to pitch up; it caused it to pitch down—disastrous in a dive. And the aircraft would begin to shake violently as its speed reached about 680 mph. Even more concerning, the wings began to lose lift.

Aeronautical engineers were certain all this was due to aircraft approaching the speed of sound—the so called sound barrier—750 mph at sea level, or in technical terms Mach 1. Our jets were not powerful enough at the time—1947—to assail this mythical barrier. Only rockets could.

Aircraft designers developed a rocket powered plane designed to break through the sound barrier—the X-1. Having learned from the ME-163’s fuel situation, the X-1 rocket plane was designed to be flown aloft and dropped from the bomb bay of a B-29 bomber.

The little rocket plane, flown by legendary test pilot Chuck Yeager, became the first craft to fly faster than the speed of sound.

The flights of the X-1 taught aeronautical engineers much about supersonic flight. So much that the next rocket plane, the X-2, had swept wings. The X-1 had straight wings. The reason wings lost lift as a plane approached Mach 1 was the air molecules cannot get out of the way fast enough and so build up in front of the wing, rather than flowing over it to generate lift. This also causes the severe vibration and the control reversal.

Swept wings overcome some of these problems because the air molecules have a chance to move out of the way as portions of the wing slice through.

To the Edge of Space

The X-2 eventually set a speed record of Mach 3.2. After the initial X series, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA which would eventually become NASA) began looking higher, and faster. In 1954 NACA developed a design for a rocket aircraft that would touch the edge of the atmosphere, and break all current speed records. It would achieve hypersonic flight.

The X-15 became the most successful of all the X craft. It flew 199 times, most successful. During those flights, it reached an altitude of more than 354,000 feet (67 miles) and speeds of Mach 6.7-4520 mph.

The B-29 was long since scrapped, so the X-15 was carried aloft under the wing of a giant B-52.

Many test pilots flew the craft. Some became astronauts. Among those was a young civilian named Neil A. Armstrong.

.

More War Weapons

As the X-15 flights proceeded, both the U.S. and the Soviet Union were fast tracking their development of rockets that could prove to be the most devastating use of rockets in history—long range ballistic missiles. Both were developing two types of missiles. One with a relatively limited range for use in a European war—an Intermediate Range Ballistic Missiles or IRBM with a range of 1500 nautical miles.

The other was a much larger and more powerful missile that could span oceans—an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile, or ICBM with a range of 5000 nautical miles.

Carrying a hydrogen bomb, either of these rockets could destroy a city.

The U.S. began its IRBM development with two rockets—the Air Force’s Thor and the Army’s Jupiter. Both used the same engine—the precursor to the H-1 with 150,000 pounds of thrust. Interestingly, the engines were uprated versions of an engine developed as the booster of a ram jet powered cruise missile—the Navaho. It never saw service because the ballistic missiles came into service quickly.

The Jupiter saw deployment first. It was in place during the Cuban missile crises. As a personal aside, we lived in Huntsville, AL at the time, just a block from Redstone Arsenal. The Jupiters, some no more than two blocks from our house, were erected and fueled, and targeted at Cuba. We weren’t sure, should they be launched, if the development would survive.

Shortly afterwards, the Pentagon limited the Army’s missiles to 200 mile distances, so the Jupiter was transferred to the Air Force. It continued service as a space launch vehicle for some time but Thor became the nation’s IRBM.

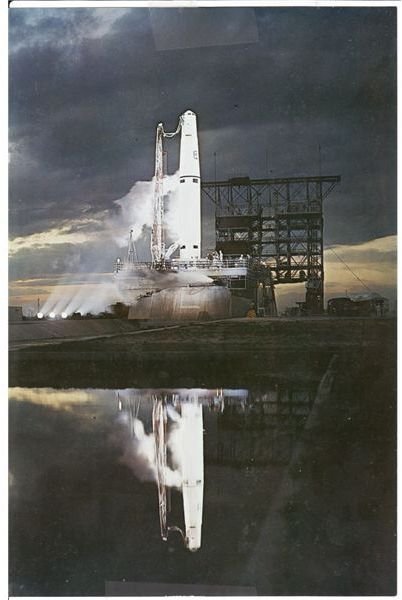

The U.S’s first ICBM was the Atlas, which would soon become its first manned space launch vehicle. This was followed quickly by the Titan I, a two stage rocket with a slightly larger payload. The Titan I was never put into use a space launcher, but its successor, the Titan II, became the launch vehicle for the Gemini spacecraft.

In part 2, we will look at today’s modern military rockets and their uses.

Sources and Credits

Navaho https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:CCAFS_Navaho_(Large).jpg

X-1 https://www.dfrc.nasa.gov/gallery/photo/X-1/Large/EC72-3431.jpg

X-2 https://www.nasa.gov/missions/research/X-2.html

X-15 https://www.nasa.gov/centers/dryden/news/FactSheets/FS-052-DFRC.html

All other photos: Personal collection

This post is part of the series: Uses of Rockets–Then and Now

Rockets have been used for many tasks for the past 2000 years. Most uses have been as weapons of war, but they have also been used to research the upper atmosphere, high speed flight, and even to take us into space.