Fine Art Photographers Bernd And Hilla Becher

Bernd and Hilla Becher

Bernd Becher was born in Siegen, Germany in 1931. Though he is best known now as a photographer, he began his art education as a painting student and then a typography student at the Kunstakademie (“Art Academy”) in Düsseldorf.

Hilla Becher was born Hilla Wobeser in 1934 in Potsdam, Germany, where she also completed an apprenticeship in photography. She also attended the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf as a painting and photography student, where she met Bernd.

Bernd and Hilla Becher began collaborating in photography in 1959 when they started their life-long project to document the vanishing industrial landscape. The Bechers also worked as freelance travel photographers and taught such students as Andreas Gursky and Candida Höfer at the Kunstakademie in the 1970s. They were married in 1961, won the Hasselblad Foundation International Award for Photography in 2004, and continued their work together until Bernd’s death in 2007.

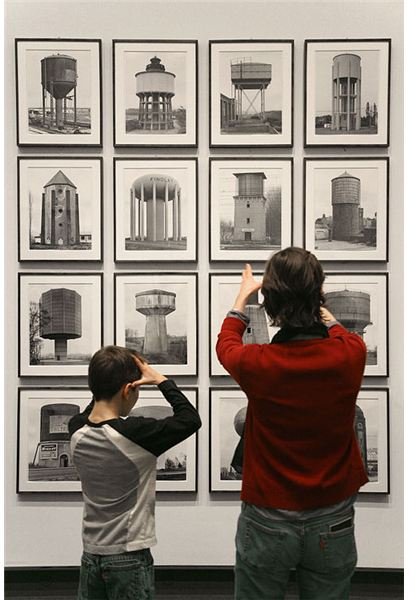

Typologies

The collaboration of Bernd and Hilla Becher began in the Ruhr Valley in Germany, where they used an 8 x 10 inch view camera to photograph the buildings and structures related to the mining industry. They used a strict formula for shooting their images: each structure was shot from the same angle and distance, they only photographed on overcast days to avoid shadows and create featureless skies, and there was a pointed lack of human presence. Their work created a systematic inventory of winding towers, store houses, water towers, silos, cooling towers, factories, warehouses, blast furnaces, houses, and other elements of the industrial landscape.

Later, the Bechers traveled elsewhere in Europe, conducting the same kind of cataloguing of industrial structures, and in 1974 they went to North America for the first time.

Initially, all of the images were contact-printed and displayed as a grid of six, nine, or sixteen 8 by 10 inch silver-gelatin prints of the same type of structure. These ordered arrangements of nearly-identical images were referred to by the Bechers as “typologies,” and the similarities of the pictures served to also bring out the differences. Both the titles of the works and the descriptions of individual images tended to be brief, stating only the type of structure, location and date; the lack of text was a deliberate choice, forcing the viewer to look at the structures as “anonymous sculptures” and not as objects in specific functional contexts.

This conceptual aspect of the Bechers’ typologies–the identification of the work as images of “anonymous sculptures” rather than as photographs per se–even resulted in the photographers being awarded the Leone d’Oro award for sculpture at the Venice Biennale in 1991.

By the late 1980s, Bernd and Hilla Becher had begun to use larger prints in their typologies, and to sometimes display single images alone.

Lasting Influence

Bernd and Hilla Becher drew influences from the preceding documentary tradition, particularly the work of Édouard Baldus, August Sander and Eugène Atget, but used an intentionally (or at least apparently) neutral viewpoint to create something like an “objectivist scientific inventory,” according to Brigitte Govignon. But they were not simply archiving a disappearing landscape; instead, their work brings out the variations and narratives of the landscape itself by presenting similar images in groups.

In many ways, the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher is as much conceptual art as it is photography, and it forced the art world to recognize that technically perfect photographs could be art. Until that time, most “art photographers” tried to divorce themselves from the medium by ignoring actual photographic principles and technical competence and instead creating pictures that were “painterly.”

Through their teaching and through the immense effect their work has had on the perception of photographs as art, the Bechers have, in turn, influenced many other important photographers. In particular, their objective attitude toward their subject matter has had an impact on such photographers as Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff, Candida Höfer and Thomas Struth. Though much of their influence has been on other German photographers, it has not been exclusively so. For example, Canadian photographer Arnaud Maggs has used an approach to photographing found objects similar to the Bechers’ typologies.

Scientific Objectivity

Whether any photograph can ever be truly objective is debatable, and has been the subject of many a heated discussion in undergraduate photography classes, but certainly the appearance of objectivity is one aspect of the Bechers’ work that has continued on in many of their students.

For a long time, art and science have been seen as belonging to two contradictory realms. The photographs of Bernd and Hilla Becher, and those they have influenced, continually question that assumption with their clinical-seeming viewpoint and their presentation of subjects in multiples. Here are some objects, these photographs seem to say, now draw your own conclusions. They invite the viewer to make science out of art and art out of science.

References

- Stimson, Blake. " The Photographic Comportment of Bernd and Hilla Becher." Tate Papers, Spring 2004. Online at http://www.tate.org.uk/research/tateresearch/tatepapers/04spring/stimson_paper.htm

- Govignon, Brigitte (editor). The Abrams Encyclopedia of Photography. Harry N. Abrams, 2004.

- Image 2 credit: Bernd and Hilla Becher, Met Museum, New York by wraggy [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

- “Bernd and Hilla Becher: Landscape/Typology.” Museum of Modern Art exhibition announcement, May 21–August 25, 2008. Online at http://www.moma.org/visit/calendar/exhibitions/95

- Image 1 credit: Hilla Becher by Leonce49 - http://www.Hans-Weingartz.de (Own work) [CC-BY-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

- 20th Century Photography: Museum Ludwig Cologne. Taschen, 2001.

- The Photography Book. Phaidon Press, 2000.