The Amusing African Penguin: Biology, Ecology & Conservation

Habitat and Distribution

The African penguin (Spheniscus demersus), also known as the black-footed penguin, or jackass penguin due to its loud braying call that sounds like a donkey, is endemic to the coast and offshore islands surrounding southern Africa. Its range stretches from Algoa Bay on the east coast of South Africa to the Namibian islands off the west coast of southern Africa. Their main breeding sites have historically been situated on offshore islands, but in recent years, they have begun colonizing land-based colonies that offer suitable habitat and a ready supply of food nearby.

Predators & Prey

The diet of the African penguin consists predominantly of pelagic fish, such as pilchard, anchovy, horse mackerel and round herring, but they also favor squid, and crustaceans to a lesser extent.

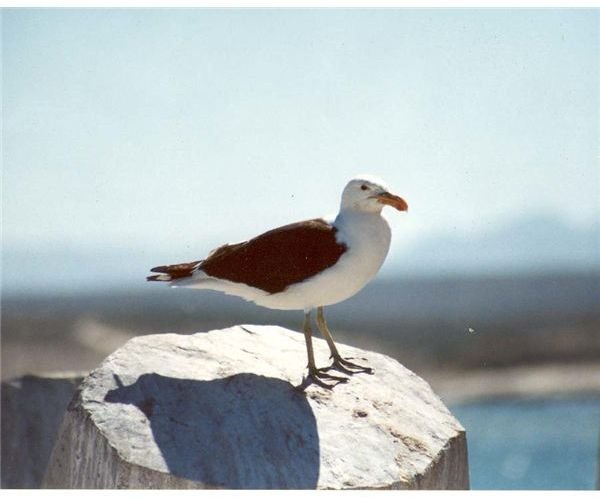

Natural predators of adult penguins include sharks, and to a lesser degree, seals. During the breeding season, kelp gulls are responsible for the highest level of predation on chicks and eggs. Mole snakes also prey on penguin chicks, while leopard and caracal have preyed on breeding adult penguins at one land-based colony. Non-indigenous animals such as dogs, cats and rats will readily prey on penguin chicks if given the opportunity and are a problem at land-based colonies and inhabited islands.

Physiology

While penguins seem rather clumsy on land, they are perfectly adapted for life at sea. They are flightless birds, so their wings are modified into flippers that they use to swim swiftly through the ocean waters. Their webbed feet act as rudders to allow them to quickly change direction at high speed when in pursuit of prey or when darting away from a fierce predator.

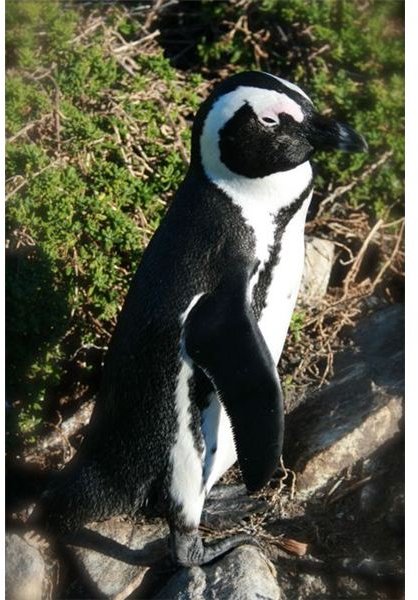

African penguins are adapted to life in cold temperate waters, with insulating fatty deposits to prevent hypothermia. Their black and white coloring provides camouflage from predators at sea, as a predator approaching from below will not readily notice the white belly of the penguin as it blends into the shimmering light coming from above, and when looking down on a penguin from above the black dorsal side blends into the shadows of the depths below. However, these adaptations cause problems of overheating while on land, incubating eggs and brooding chicks during the breeding season. In South Africa, they are often exposed to high temperatures rising up to 90 degrees F (32 degrees C) and higher in late summer; and during winter on the Namibian islands when hot, dry, easterly winds frequently blow from the desert.

Annual Cycle

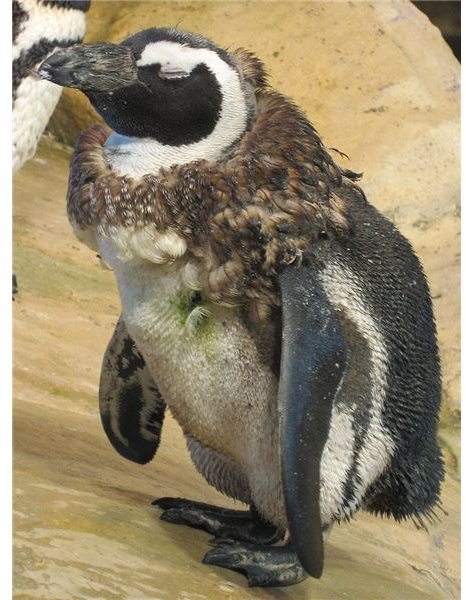

African penguins typically molt between November and January. During this time, they are land-bound for 21 days, as they do not have the protection of their waterproof plumage against the cold and damp. For this reason, the penguins go on a pre-molt feeding binge, where they spend roughly five weeks at sea around feeding grounds, fattening up before returning to land to molt. Their weight increases to about a third more than their normal body mass, but these fat reserves are depleted over the three week molting period. When it has completed molting, the rather gaunt looking penguin has its sleek new waterproof plumage, and then returns to the sea for six weeks to feed and replenish energy stores, leaving the colonies rather deserted over the peak summer period.

Reproduction

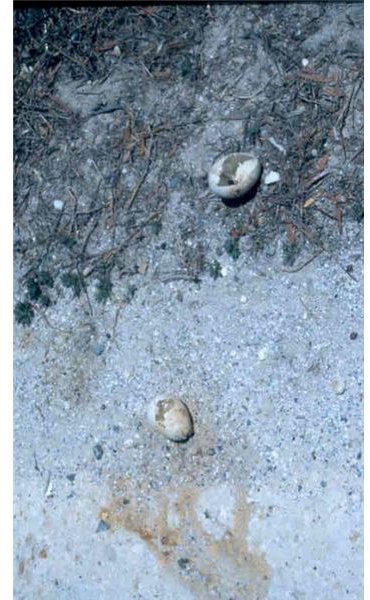

The breeding season starts in late summer, shortly after the birds return to the colonies following their post-molt feeding period. Breeding pairs start prospecting for nests late January/February. Depending on the terrain, the breeding pairs will scrape burrows out of hard soil under bushy thickets, or make their nests in rock crevices, which they then line with feathers, dried seaweed, twigs and other flotsam and jetsam.

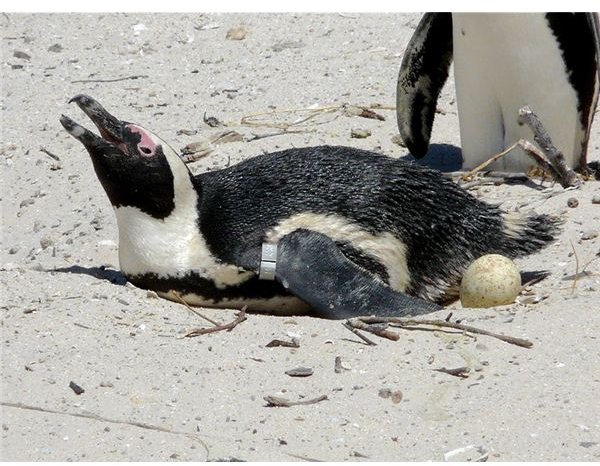

Penguins are very enterprising, and on the Robben Island colony old, unused buildings are often used by penguins to set up home. The female lays a clutch of one to two eggs, with usually only one chick surviving. This is frequently followed by mass abandonment of eggs during heat waves in February/March, when it is not unusual for an entire colony to abandon their nests due to heat stress. Signs of heat stress in an incubating penguin include an open beak and possibly panting, the fleshy part around the eyes turning a dark pink, and a penguin standing up with its wings stretched out as the bird tries to thermoregulate. Should the penguins abandon their nests, they do however, return for a second breeding attempt, with breeding peaking over the winter months between April to August, with second or third clutch chicks often fledging as late as October when pairs have more than one clutch of eggs per season.

The male and female take turns on the nest, one incubating the eggs while the other goes out to sea to feed. The eggs hatch after 38-41 days, revealing chicks covered in a mass of fluffy grey down. This is eventually replaced by waterproof plumage in its juvenile stage, where it remains a dull grey and white color (where it is referred to as a “blue”) until it acquires its striking black and white adult plumage after first molt (anywhere between 12 and 22 months of age).

African penguins are generally considered monogomous, keeping the same breeding partner year after year. They also tend to exhibit nest fidelity and return to the same nesting site as the previous breeding season.

Conservation Status

African penguins were upgraded from being listed as “Vulnerable” to being listed as “Endangered” in the IUCN Red Data Book in 2010, following a dramatic drop in the total population.

In the early 1900s the total population of African penguins was estimated to be around 2 million individuals. In 1956 this had been reduced to around 147,000 pairs. The 2010 population census revealed that the African penguin population had been reduced to an estimated 21,000 pairs – a reduction of more than 100,000 pairs in just over 50 years.

Conservation Threats

Causes for the decline in the African penguin population include:

• Guano scraping for fertilizer (now prohibited). Breeding penguins scrape burrows out of the guano deposits to shelter their eggs and young from gulls, and other predators on the barren islands. These burrows also prevent heat stress and thus nest desertions. Although the harvesting of guano was prohibited many years ago, the effects of this practice is still having a huge impact on the penguins today as they are left with sub-optimal breeding sites.

• Egg collecting for culinary purposes (now prohibited). In the past, penguin eggs were relished as a delicacy and the mass collection of eggs from colonies prevented fresh batches of young from evolving into breeding adults, thus completely disrupting the breeding cycle, and having a negative impact on population growth of this species.

• Colonizing of their breeding islands by increasing Cape fur seal populations, has forced penguins off many of their historic breeding sites.

• Diseases such as Newcastle disease and avian malaria have had severe impacts on certain colonies in the past, and remain a threat, particularly amongst the mainland colonies.

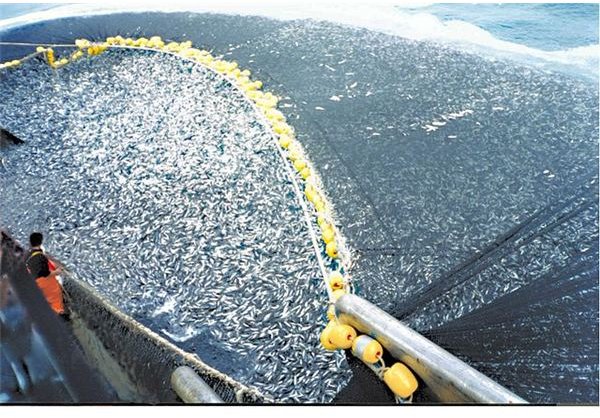

• Food shortages due to overfishing of pilchard and anchovy, the natural diet of these birds, causes higher mortality rates due to starvation, and reduces chick survival.

• Oil pollution is a constant threat as winter storms frequently bring rough seas, leading to ships running aground or sinking off the southern African coast. Should a penguin become oiled, its plumage loses its water-resistant properties. This causes the feathers to become sodden, leading to death from hypothermia. The birds tend to remain on shore to prevent this, but then slowly starve to death as they cannot go to sea to feed in this state. The oil is also poisonous if ingested and causes many fatalities this way. As the winter storms coincide with the African penguin breeding season, an oil spill can result in breeding failure and chick mortality due to the disruption to breeding as surviving oiled parent birds are removed from the islands for cleaning.

Continue reading on page 2 to find out more about the effects of global warming on the African penguin, and conservation measures that are being adopted to save this animal form becoming extinct.

Global Warming

The full impact of global warming on our environment and wildlife is not yet completely understood. However, it is becoming more and more apparent that the consequences for some habitats and the species that dwell therein will be dire. This is especially true of species that depend on cooler climates for their survival, such as the penguins of the Antarctic regions in the south, as well as those that reside in the temperate regions, such as the African penguin.

Two crucial issues associated with global warming include a rise in sea surface temperature and a rise in ambient air temperature. Increased sea surface temperatures will reduce productivity of the oceans and thus limit food availability, negatively impacting all predatory species, including penguins. Similarly, an increase in ambient temperatures will lead to increased heat stress during incubation resulting in nests being abandoned and a reduction in breeding success. The African penguin lives in one of the warmest environments of any species of penguin, and is already severely compromised by food shortages and heat stress during breeding, and thus global warming poses a very real threat to the future survival of this species.

Management Strategies & Conservation Measures

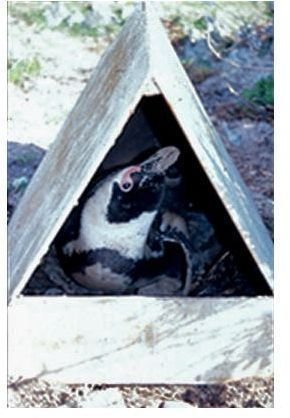

Providing a Suitable Breeding Habitat

Research on the use of artificial nest sites has been conducted in various African penguin colonies in an effort to reduce heat stress of incubating birds to prevent the birds abandoning their nests, aiming to ultimately improve breeding success. Various forms of artificial nest boxes have been explored - wooden nest boxes deployed on Robben Island were unsuccessful at reducing temperature fluctuations, and while fiberglass dome-shaped burrows deployed on Dyer Island provide protection against predators and rain, they are also inclined to get uncomfortably hot in summer. Jessica Kemper, a former PhD student with the Animal Demography Unit at the University of Cape Town, compared breeding success in surface nesting African penguins breeding on Namibian islands, to those nesting in artificial nests made from plastic drums cut in half that were buried into the ground to form a burrow-like structure. The bins were spacious enough to accommodate a breeding pair of adult penguins and two large fledgelings, were well drained, and provided suitable protection from the harsh environmental conditions, and limited predation by kelp gulls. Her results showed that the birds breeding in bins were the most successful.

Fisheries Management

WWF have teamed up with four major stakeholders in the fishing industry to form the Responsible Fishing Alliance (RFA) with a view of adopting an Ecoystems Approach to Fisheries (EAF) management to ensure the long-term conservation of marine resouces. According to the WWF, “An EAF seeks to protect and enhance the health of marine ecosystems on which life and human benefits depend. The approach depends on balancing the diverse needs and values of both present and future generations. (…) The goals of the Alliance include promoting responsible fisheries practices, influencing policy on fishery governance, skills development to enable the implementation of an Ecosystem Approach and facilitating high quality ecological, socio-economic and governance related research to inform the implementation of an EAF.”

The RFA recently funded a research project, conducted by the Animal Demography Unit at the University of Cape Town, on the amount of fish removed from the oceans each year by African Penguins. In this study, penguins were injected with doubly labelled water to estimate their energy consumption, and fitted with GPS data loggers to determine how much time they spent on land and foraging at sea. After a complex analysis of the data collected, the results show that individual adult penguins consume approximately 174 pounds (79 kg) of anchovy during the breeding season. In addition, it takes 50 pounds (23 kg) of anchovy to produce a chick weighing 6.6 pounds (3 kg). They estimate that individual adult penguins consume a further 406 pounds (184 kg) of anchovies throughout the rest of the year when they are not breeding. These results show that a breeding pair of penguins, feeding only on anchovy, require a total of 1257 pounds (570 kg) of fish for the year to successfully raise two chicks. This research provides scientists, conservationists and fisheries managers with a better understanding of the food requirements of penguins and it is a valuable tool for implementing fisheries management strategies in accordance with marine conservation goals.

SANCCOB (South African Foundation for Conservation of Coastal Birds)

The magnitude of the threat oil poses was experienced in June 1994 when the slick from the Apollo Sea enveloped the shores of the Cape Peninsula and surrounding islands. Here over 10,000 penguins were affected, with over 4,000 being successfully treated and released by SANCCOB. In July 2000, the sinking of the Treasure resulted in the removal of close to 40,000 breeding penguins from Dassen Island and Robben Island, both major breeding colonies. Of these, 19,000 penguins were treated for oiling, with 16,000 successfully rehabilitated and released by SANCCOB (South African Foundation for Conservation of Coastal Birds). The remaining 20,000 “clean” penguins were trucked further up the East coast where they were released, in an effort to prevent them from getting oiled while clean-up efforts were underway. The rehabilitation of oiled penguins is not only undertaken for the welfare of oiled individuals, but it is vitally important for the long-term conservation of the African penguin, which just cannot afford to have mass mortalities on this scale.

Prognosis

Considering that the estimated total number of breeding African penguins in 2010 is equivalent to the number of penguins rescued in the Treasure oil spill just 10 years earlier, is cause for grave concern. Due to a number of factors, the population has halved in a decade. The only chance we have to stop this endearing little penguin from going extinct is to take a holistic approach to conservation and fisheries management for the health of our marine ecosystems. The African penguin is a flagship species in the southern African marine ecosystem, and by drawing attention to the plight of this conservation-worthy species, it is hoped we can not only save it from extinction, but also prevent other marine species from becoming endangered too.

Resources

Dyer Island Conservation Trust, https://www.dict.org.za/penguin.php

IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.1. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 16 June 2011. https://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/144810/0

Kemper, J. 2001. African Penguins and rubbish bins: population dynamics and conservation in Namibia. Bird Numbers 10(2): 25-26. https://web.uct.ac.za/depts/stats/adu/bn10_2_00.htm

Randall, R.M. 1995. Jackass Penguins. In: Payne, A.I.L. & Crawford, R.J.M. (eds). Oceans of Life off Southern Africa. Halfway House: Vlaeberg. pp. 234-256.

Underhill, Les. “Today is World Oceans Day - how much fish do penguins remove from the oceans per year?”, https://adu.org.za/news_list_all.php

WWF. “South Africa lauches first-time fishing alliance”, https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?174222/South-Africa-launches-first-time-fishing-alliance

Image Credits

African Penguin Distribution Map: By Nrg800 [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons

African Penguin Moulting: By Liné1 [GFDL (www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC-BY-2.5 (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons

Heat Stressed Penguin on Nest: By Mike Scott [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

African penguin, near Boulders Beach, South Africa: By Paul Mannix [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Global Warming Graphic: By MikeEdwards [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)] ,via Wikimedia Commons

Overfishing: By C. Ortiz Rojas/NOAA [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

All other images supplied by author.