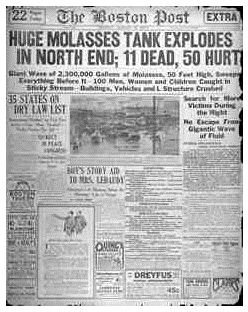

The Boston Molasses Disaster: Causes of the Molasses Tank Explosion

The Boston Molasses flood, also known as the Boston Molasses disaster, was a bizarre event that continues to evoke interest nearly 100 years after the fact. It was not quite the sticky, humorous occurrence that one might expect; in fact, the molasses tank explosion and resulting flood killed 21 people and injured another 150. It also destroyed a number of houses and drowned many horses. Investigators were never able to conclusively determine the Molasses disaster’s cause, but they advanced several theories that give a better view into just what happened on that fateful day. Today, the disaster has entered into local legend, and Boston tour guides often show tourists the site of the disaster, which they sometimes call “The Boston Molassacre.”

The Explosion and Ensuing Flood

The explosion occurred at around noon on January 15, 1919. Survivors recall the day as being unseasonably warm. The epicenter of the disaster was the Purity Distilling Company, a firm whose specialty was the production of ethyl alcohol. Ethyl alcohol and rum can be made from the fermentation of molasses; the molasses in the tank that exploded was intended for distillation into ethyl alcohol. Though Prohibition was about to take hold in the United States, Purity Distilling Company was free to produce alcohol as it was a component of munitions of the day.

At the time of the explosion, workers would have been enjoying their lunch breaks. No one, therefore, was watching as the molasses tank exploded. Many heard the explosion, though; they described the noise as resembling a machine gun. This machine gun-like roar came from the rivets that held the tank together bursting apart. As the tank came apart, witnesses reported that the ground shook as if from the passage of a nearby train.

The reason for the Boston Molasses Disaster’s destructiveness was the sheer size of the molasses tank that exploded. The tank, which stood at 529 Commercial Street (by Keany Square), was 50 feet high and had a diameter of 90 feet. At the time of the disaster, the tank was nearly full; it held 2.3 million gallons of molasses.

With the rupture of the tank, a wave standing as high as 15 feet was unleashed, sweeping outward onto the streets. Contrary to molasses’ slow-moving reputation, the wave sped outward at an estimated speed of 35 miles per hour. The high density and viscosity of molasses contributed to the massive destructive power of the molasses wave, which exerted a pressure of around 2,000 pounds per square foot (about twice atmospheric pressure).

This high pressure, in addition to the wave’s immense speed, destroyed just about everything in the immediate vicinity. Girders on the nearby elevated rail platform were mangled; meanwhile, a train was lifted off the tracks. The wave also knocked a number of houses off of their foundations, and crushed others. One woman, Bridget Clougherty, was killed after her home collapsed on her. Further away, a truck was tossed into Boston Harbor.

The wave was made up of more than just molasses. It also carried large shards of metal from the ruptured tank along with it, which wreaked havoc as the wave spread outward. One such shard took out a freight house on its journey, killing several workers who had been inside it.

Causes of the Boston Molasses Disaster

The cause of the molasses tank explosion at Purity Distilling Company was never definitively determined. The company owners, for their part, held that the culprit had been a bomb placed inside the tank by anarchists. Though somewhat absurd on its face, this argument is not inconceivable: the molasses was being fermented for use by the US Army, and bomb attacks were not totally unheard of at the time. Still, investigators found no evidence of a bomb, so this theory is more or less ruled out.

The other theories were that an explosion had occurred inside the tank, prompted by gaseous byproducts of fermentation; and that a structural failure had occurred in the tank, which was only four years old at the time. Inspectors ultimately concluded that the latter theory best explained the molasses explosion.

Carbon dioxide buildup was at least partially responsible for the tank’s failure, though. A large increase in temperature over the previous day (from 2 to 40 degrees F) would have exacerbated this pressure buildup.

The location of the failure was by a manhole; inspectors suspect a crack propagated there until it reached criticality, unleashing the massive volume of molasses all at once. This crack may have been caused by fatigue, and the tank certainly would have been subjected to fatigue-inducing circumstances, as the tank was filled and drained repeatedly (thus creating a cyclical load). The hoop stress was likely the culprit here. Indeed, hoop stress is largest at the base of a filled tank, where the manhole cover was located.

The investigation of the disaster dragged on four years, with many lawsuits being filed by victims’ families. Finally, the court determined that the factor of safety had been too low. Essentially, the construction had been poorly managed, and the container was not actually safe at full volumes. Further investigation showed that Arthur Jell, the construction manager, had not performed any standard safety tests like checking for leaks. Reportedly, the tank was always leaky, and was painted brown by workers to hide this fault.

This failure was, apparently, totally avoidable. The Boston Molasses disaster was essentially caused by negligence and poor engineering; a properly designed tank should have had a factor of safety large enough to withstand complete loading.

Above: Damaged El train structure, complete with a piece of the molasses container.

Aftermath of the Flood

In the end, 21 people were killed in this disaster, plus an uncounted number of horses. Rescuers took days to uncover the last victims, who were so coated with molasses that they were difficult to identify. It is estimated that workers took about 87,000 man hours to clean up the molasses spill. Cleanup was no small feat, as areas around the spill were flooded with as much as 3 feet of molasses. Work crews tried to get rid of the sticky mass by spraying it with hoses and coating it with sand. Inevitably, the molasses spread around the city, and for months afterwards many surfaces in Boston were sticky. Runoff from the streets turned the harbor brown, and it remained so until the end of the following summer.

Families of the victims brought a class-action lawsuit against the United States Industrial Alcohol Company, which had purchased Purity Distilling Co. in 1917. This class action suit was one of the first of its kind in Massachusetts, and the court ultimately ruled in the victims’ favor. United States Industrial Alcohol Company was forced to pay out approximately $600,000 to victims’ families. In today’s dollars, that’s over $6,000,000.

The USIAC did not rebuild the tank after the Boston Molasses Disaster. Today a park stands at the former location of the holding tank. Called Langone Park, the area has several baseball fields. The Bostonian Society has placed a plaque at the entrance of a nearby park, Puopolo Park. The plaque reads,

“On January 15, 1919, a molasses tank at 529 Commercial Street exploded under pressure, killing 21 people. A 40-foot wave of molasses buckled the elevated railroad tracks, crushed buildings and inundated the neighborhood. Structural defects in the tank combined with unseasonably warm temperatures contributed to the disaster.”

There is little other sign of the disaster, though legend has it that Boston still smells of molasses to this day.

List of Victims

The disaster claimed 21 lives. Most of those killed were workers in the tank’s immediate vicinity.

- Patrick Breen, age 44

- William Brogan, age 61

- Bridget Clougherty, age 65

- Stephen Clougherty, age 34

- John Callahan, age 43

- Maria Distasio, age 10

- William Duffy, age 58

- Peter Francis, age 64

- Flamino Gallerani, age 37

- Pasquale Iantosca, age 10

- James H. Kinneally, age unknown

- Eric Laird, age 17

- George Layhe, age 38

- James Lennon, age 64

- Ralph Martin, age 21

- James McMullen, age 46

- Cesar Nicolo, age 32

- Thomas Noonan, age 43

- Peter Shaughnessy, age 18

- John M. Seiberlich, age 69

- Michael Sinnott, age 76

Sources

Image: Wikimedia Foundation - Boston post-January 16, 1919

Image: Wikimedia Foundation - Boston Molasses Disaster

Image: Flickr - Technicool - As Slow As Molasses

Image: Wikimedia Foundation - el train structure

Massachusetts Historical Society - What caused the great Boston Molasses Flood?

Eric Postpischil’s Personal Page - [Without Warning, Molasses in January Surged Over Boston](/tools/Without Warning, Molasses in January Surged Over Boston) - (Online reprint) by Edwards Park

Boston Online - The Great Molasses Flood